Table of Contents

Citations

Plagiarism

Dichiarazione

Plagiarized-text

Commentary on a collect

Inset citations

Citations

Indirect discourse

Citations

All of the work involved in giving citations correctly suggests that citations are not to be made lightly. Really, the scholar is to write the paper based on his or her findings, interpretation and chosen method of presenting an argument. The paper is to present the scholar’s own work, not the work of others.

There are several resons for citing the text of another, including the following:

- Authority: sometimes a reference to the work of another is warranted to present an authoritative source, such as a statement on the divine-human exchange given by Irenaeus of Lyon or Athanasius.

- Clarity: Sometimes another author has presented some ideas with such clarity that bears repeating, as for example the translations of the prayers published by the instructor.

- Foundation: Sometimes the student wishes to present the argument of another as a basis for developing the student’s own argument.

- Contrast: Sometimes the student wishes to contrast the writing of another with the student’s own ideas.

Plagiarism

Not citing the work of others correctly is considered plagiarism and, according to the policy of the Registrar (Segreteria), may result in dismissal of the student or the revocation of the student’s diploma.

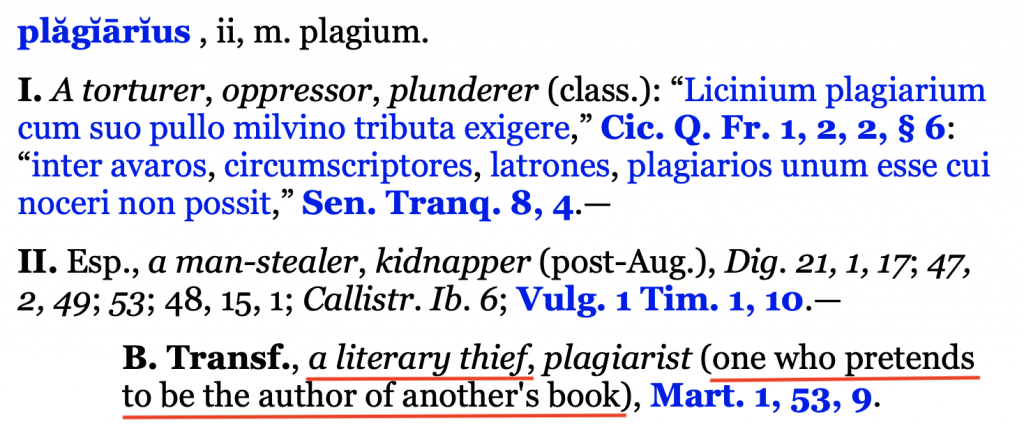

The word “plagiarism” comes from the Latin word plagiarius, whose definition is provided below from the Lewis and Short Latin dictionary.

The meaning we are using here is found in the above definition under Roman numeral II. B. where the transfered meaning is given: “a literary thief”. This is further explained as “one who pretends to be the author of another’s book”. This occurs when I take the text of someone else, put into my writing without acknowledging the source and so pretend that I wrote it.

I believe the situation here is typically not one of malicious intent but one that comes from the convergence of different cultures. The ancient Roman tradition of teaching comes from the Latin word traditio, “a handing down, a tradition; instruction”, whereby the teacher imparts and the student repeats the words of the instructor. Some of our students come from an oral culture and must learn the traditions of a written culture. Other students come from a culture where respect is shown by repeating the words of instructors and elders as one’s own words. For such respect to work in an academic culture, however, the source of the words must be acknowledged properly. Some of our students are accustomed to taking oral exams and are not accustomed to submitting written work, when new skills must be introduced, learned and eventually mastered.

Sometimes students have both properly quoted texts from other authors and cited the source in a footnote, but without introducing the other author or the source of the citation and without giving a summary of the elements in the quotation that are important to the student’s own writing. It is as if the student is using the words of another author to write the student’s own paper and this without any further critical reflection. This is a greater temptation when a person is writing in a language in which a person is not fully comfortable writing. Such will not do in scientific writing. In short, the student is not to use another person’s writing to present the student’s own thought. Do not let the writing of others do your work for you.

Rather, this is your paper and you are presenting your own argument to the reader. Take charge of your own argument. By distinguishing the writing of other authors, the student will also come to the fore as a distinct voice and contribution.

In short, the student writing a paper is primarily in dialogue with the reader. Sometimes the student may wish to reflect critically on the writing of another author and to present this critical reflection to the reader.

There are several reasons for citing the work of another. Perhaps the work cited was written by an authoritative source. The author of a paper may wish to use the authority of another work as a basis for one’s own writing, as I cited the definition of plagiarius from the Lewis and Short Latin dictionary above. Conversely the author may wish to challenge the authoritative statement and offer a different perspective. In either case the writer of the paper is entering into a dialogue with the author of the citation.

As a dialogue, the writer of the paper should introduce the author of the citation and the original context where the citation was found. This could include the title of the original work, the situation addressed in the original work, the concerns of the original author, the purpose for writing of the original author. In such ways the author and original context of the citation is respected.

The writer of a paper should not expect the reader to understand which parts of the citation are important to the argument. Rather, the writer of a paper should tell the reader how a citation fits into the argument of the paper, as I did in the paragraph following the citation of the Lewis and Short Latin dictionary above. The writer could first describe the authority of the author and then give the citation. The writer could describe the original context of the citation and then apply the citation to a different context. The writer could present the value of the citation and then challenge some aspect of it. Such examples all indicate the the writer is engaging in a conversation with the author of the citation.

If the writer of a paper is simply using the words of another person to express the writer’s own ideas, then there is no dialogue with the author of a citation, nor is there anything original.

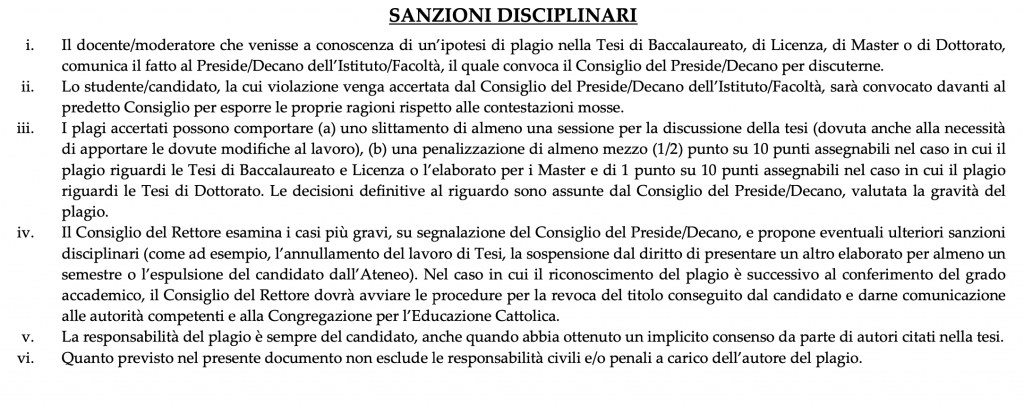

Dichiarazione di originalità del testo e di non plagio

When students at the PIL submit a proposal for a license dissertation (tesina), they are required to submit a declaration of the originality of their written work and of not plagiarizing. This text can be downloaded from the web-site of the Athenaeum and should be read by students preparing any written work. It can be found by following the following instructions.

Go to the web-site: http://www.anselmianum.com

The PDF document will automatically download. Here is a link to the current document as of 28 March 2020. Please find the following heading and text.

Plagiarized text

Here is an example of a plagiarized text I received from a student who shall remain anonymous.

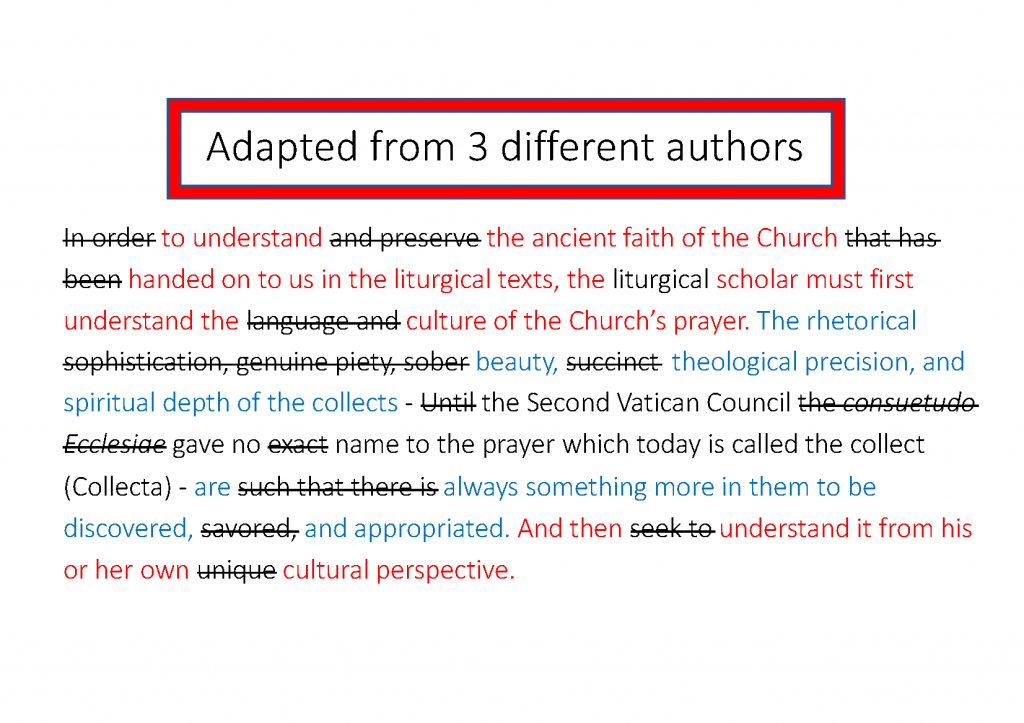

The same text is given below with indications of the four different authors.

The above image indicates the writing of four different authors in thie text. The text in red was taken from one source, the text in blue from another, the text in black from a third. I have indicated the writing of the student in black letters with a line drawn through the words. You can see that the student added a few words here and there to connect the other texts and to make it seem as if the plagiarized texts were revised sufficiently to make them the student’s own writing. In doing this, the student

- has not shown respect for the thought of others by citing it,

- has not entered into a dialogue with any of the other authors,

- has not shown any critical thinking or thought of his or her own,

- has not contributed anything original,

- has not developed his or her own argument,

- but simply pasted together the thoughts of others,

- who may in fact disagree with one another.

Commentary on a collect

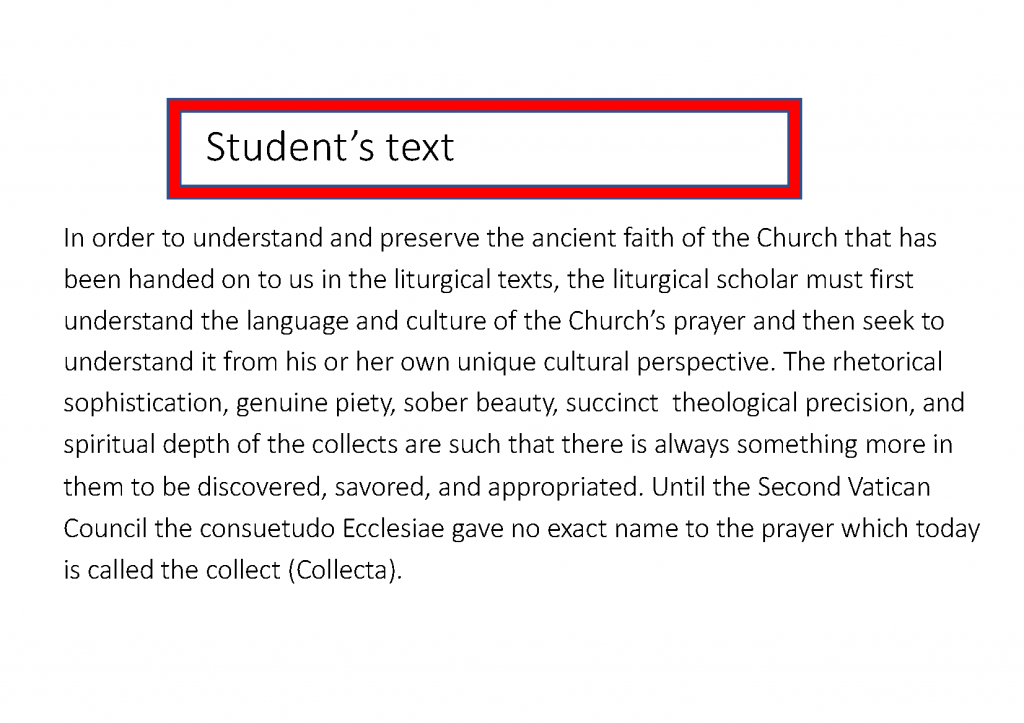

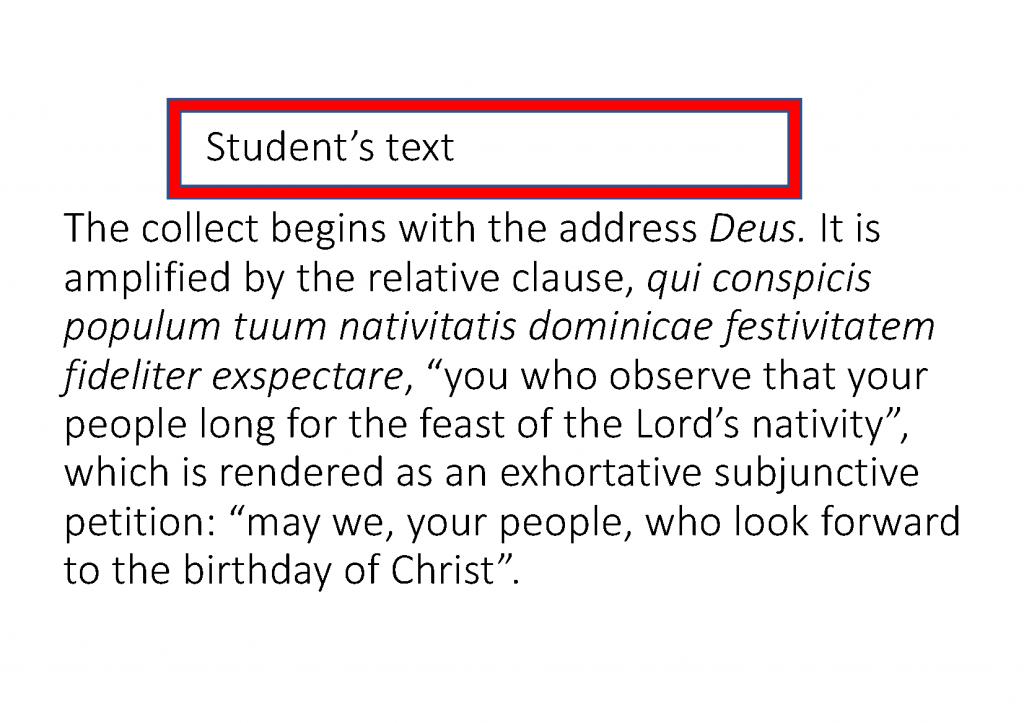

Here is another text submitted to me by a student who shall remain anonymous.

The above text is a blending of four different authors as shown below.

The first line, given in black letters, was written by the student. The text in read was originally published by the instructor. The text in darker blue is from the Missale Romanum of 2002. The text at the bottom in lighter blue is from the Roman Missal of 1974. Beyond that, there are other difficulties with this text, as seen in the next image.

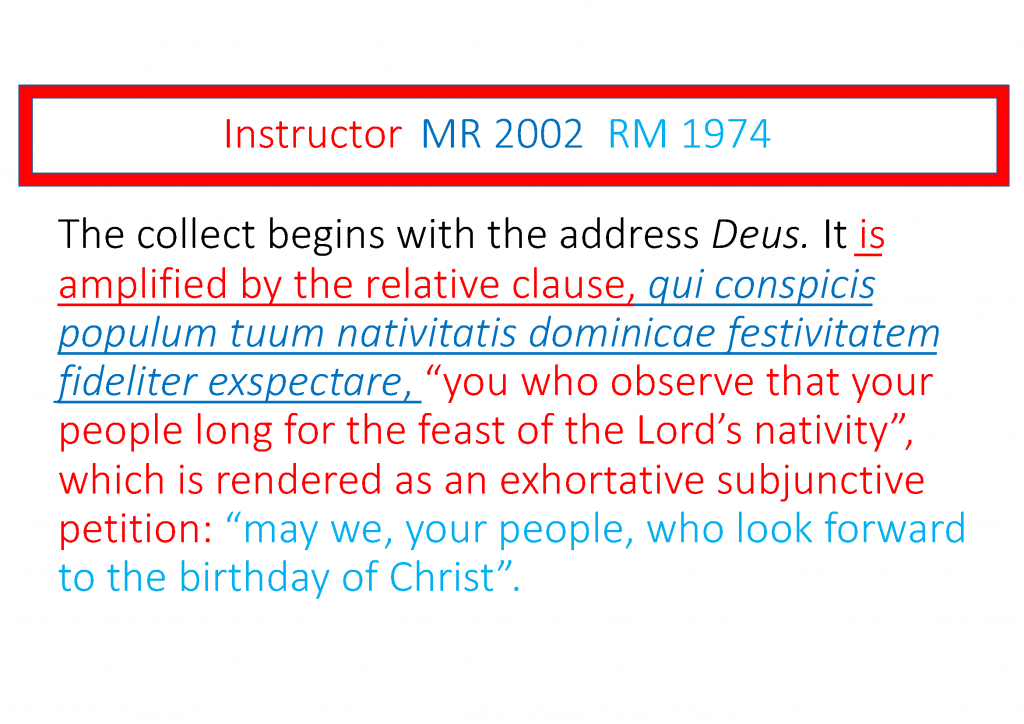

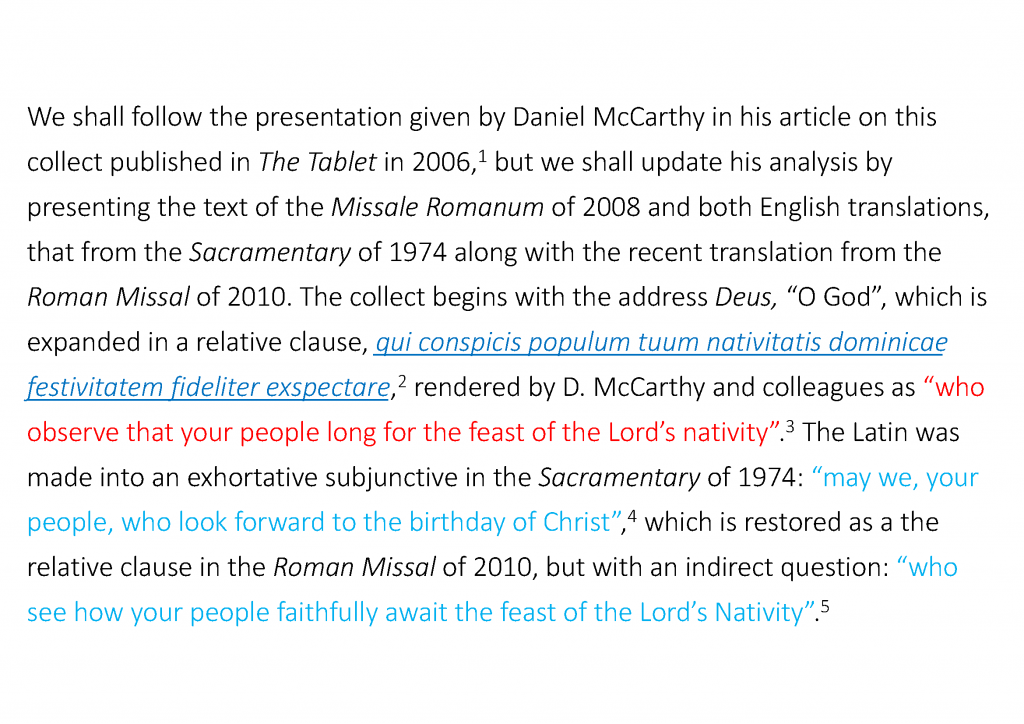

In the above image the student gives the instructor’s English translation of the Latin text of the prayer, presented here in red letters, without acknowling that the instructor produced this translation with Reginald Foster and James Leachman. Worse yet, the student did not quote the instructor’s translation correctly. The student added the word “you” at the beginning of the quote, which is not present in the instructor’s text which begins “who …”. Furthermore, when the instructor wrote the original commentary in 2006, the instructor quoted the then current Missale Romanum of 2002, whereas the student writing in 2019 should have cited the text from the Missale Romanum of 2008, which is the same text but requires a different citation. The last two lines of the text present a further difficulty.

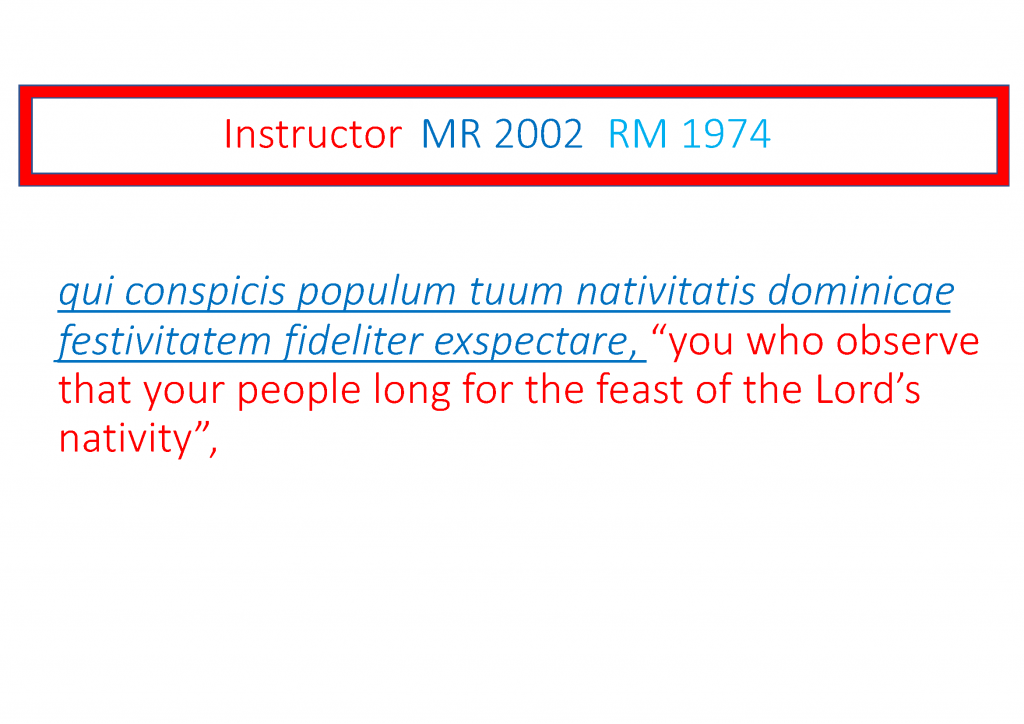

The text above is from the instructor’s original publication in 2006, in which the instructor cited the then current text of the Roman Missal of 1974. The student writing in 2019 could have cited this same translation, but certainly should have cited the more recent translation from the Roman Missal of 2010. In this way the student would have brought the commentary up to date. The following image is given as a minimal suggestion of how the student could have written the text. The text of the instructor’s translation, given in red letters, has been corrected and the footnotes follow.

In the first part of the text above, the text in black letters, student acknowledges that he or she is following the structure of the argument established by the instructior in the article published in 2006. The new text was composed by the student, and the only direct quote from the instructor is the instructor’s proper contribution to the discussion, the English translation developed in collaboration with Reginald Foster and James Leachman. The student quotes the same Sacramentary of 1974, but now sets it in comparrision with the text from the Roman Missal of 2010. In this way the student respects the instructor’s contribution made in its time and then becomes a dialogue partner by continuing the conversation in the student’s own time. Of course the student would not need to underscore or colour any of the text as done above have for ease of reviewing.

Inset citations

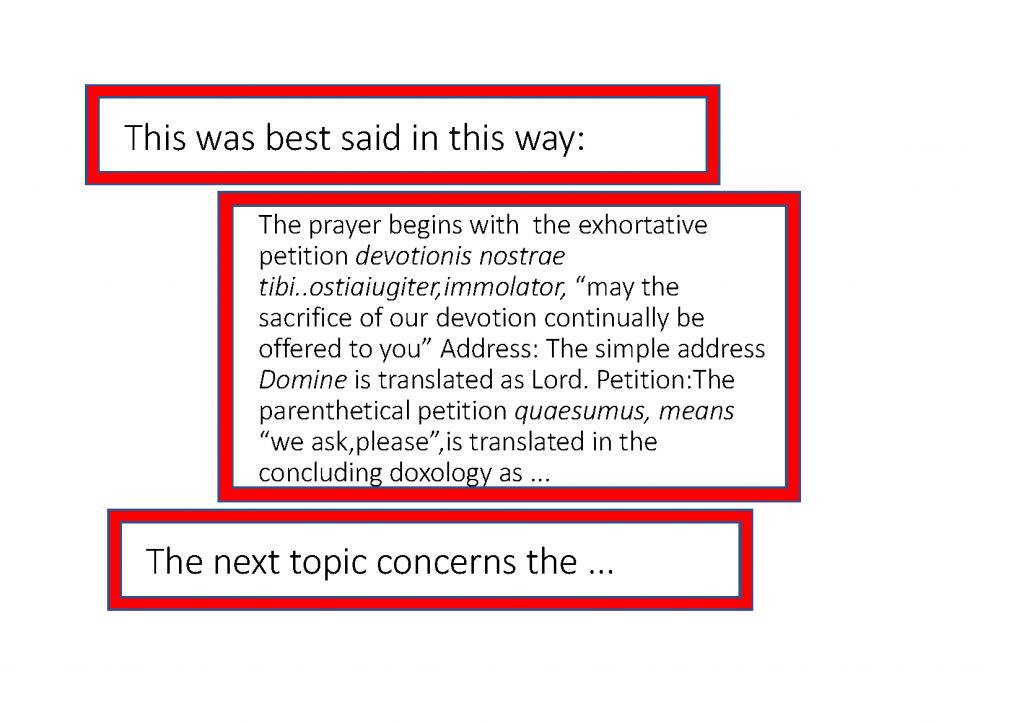

A third example of a student’s writing is useful for understanding how to introduce and follow up on an inset citation. A student who shall remain anonymous submitted the following. I have shown the structural elements with red blocks.

The top red square provides somewhat of an introduction to the text, but it raises the following questions:

- Who said it in this way?

- Where did he or she say it? To whom? On what occasion?

- What concern was the author addressing?

- When did he or she say it?

- Why is it best said in this way

- No introduction of the original context of the statement is given.

- The student writing the paper uses the citation to speak for the student,

- without distinguishing the original context from the student’s context.

The middle red square above gives the citation, but in a problematic way.

- The original text begins a paragraph so the first line is further indented, as should the first line of the indented quote.

- The citation must replicate exactly what the original text said.

- The line divisions do not have to follow original prose text.

- But prayers and poetry must follow the original line divisions.

- There are numerous typographical errors – and the student is quoting the instructor!

The bottom red box above gives the beginning of the next paragraph, which moves on to the next subject, which is also problematic.

- The student does not enter into any dialogue with the author of the citation.

- The next paragraph immediately moves on to a new topic.

- This means that the quoted text talks for the student.

- No distinction is acknowledged between the student’s argument and the quoted argument – but there is!

- The cited text was first said to others, in another place, on another occassion. Not to the person reading this text.

- There is no indication of when in history the citation was said, and the student is not updating the information.

- The writer should tell the reader why this is the best way to say it.

- The writer is requiring the reader to figure out what is important in the citation for the argument presented in this paper.

- The student has lost one’s own argument.

- The student is not showing any critical awareness or thought.

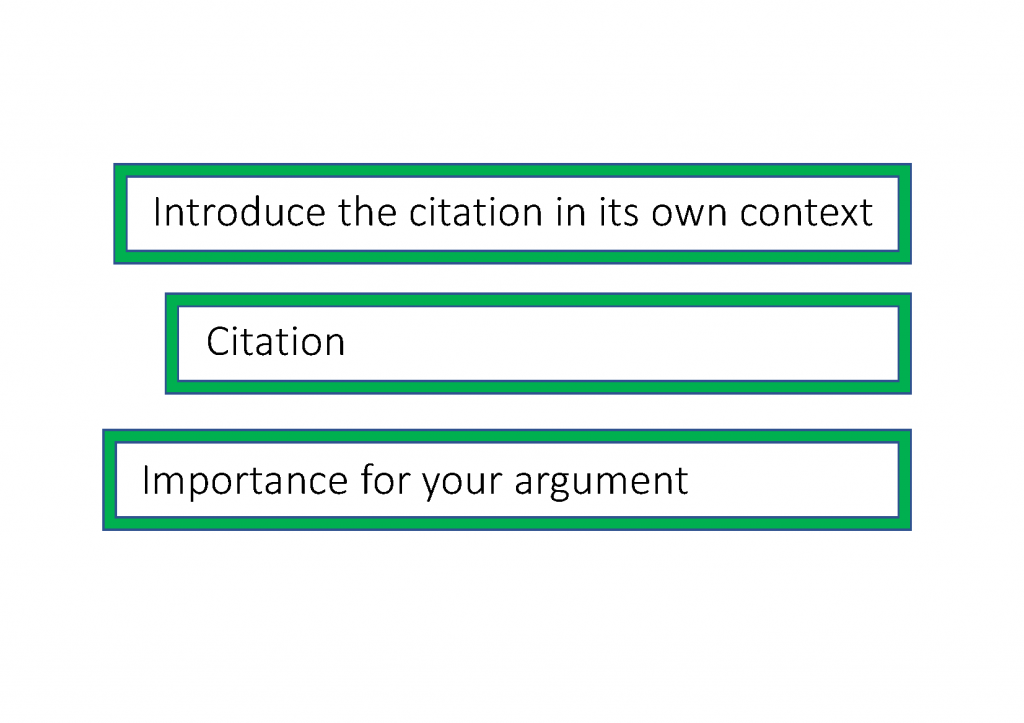

The good use of a citation involves three elements indicated in green boxes in the following image.

The top green box indicates the writer’s introduction of the citation. The following are given as indications of how an author might introduce a cited text.

- Identify the author who wrote it, said it, recorded it, drew it, created it.

- Tell why the reader should trust this author. For example, because he is a professor of the material at the Pontifical Oriental Institute.

- State the context in which the author said the citation by giving the title of the book or article or the spoken address at a named event.

- State when in history the author wrote or said it?

- State why the author wrote or said it. Was the author addressing a specific concern or was it part of an ongoing conversation

My rule for direct citations is: if I use three words or more in a row from another author, then I put them in quotation marks, either when writing in English “…” or when writing in Italian « … », and give a footnote citing the source of the text. The quotation should be only as long as is necessary for the student to make the points needed for the student’s own argument.

If the citation is several lines long, then the entire text is indented, and no quotation marks are used, as for example this text is indented. A footnote citation is given at the end of the indented text.

The second greek box above indicates the citation itself. Keep the following in mind when selecting the citation.

- Reproduce only the text that is important for your argument.

- Reproduce it exactly.

- If the original begins a paragraph, make it so here; likewise if it is a heading

- In prose you can change the line breaks.

- Preserve the line breaks for prayers and poetry as much as possible.

- If there is an error in the original, after the error put [sic], “thus” = that is how it was written.

- Do not introduce your own typing errors into the instructor’s writing!

The context of the original quoted statement is given in the introduction. So, following the cited statement, in the bottom green box shown above, the writer show the reader why the quote is important for the author’s own argument. Please keep the following in mind.

- State the points that are important.

- If the quote is from an earlier stage in the historical conversation the writer may want to update the reader on the more recent developments in the conversation.

- The writer may want to compare and contrast the citation with something already said, or use the citation as a preparation for something the writer is about to say.

- The writer may want to state the points of disagreement with the quote.

- The writer should show one’s own critical thought and assessment, while being respectful of the thought of others.

- The writer may show one’s own reflection and consideration of the situation.

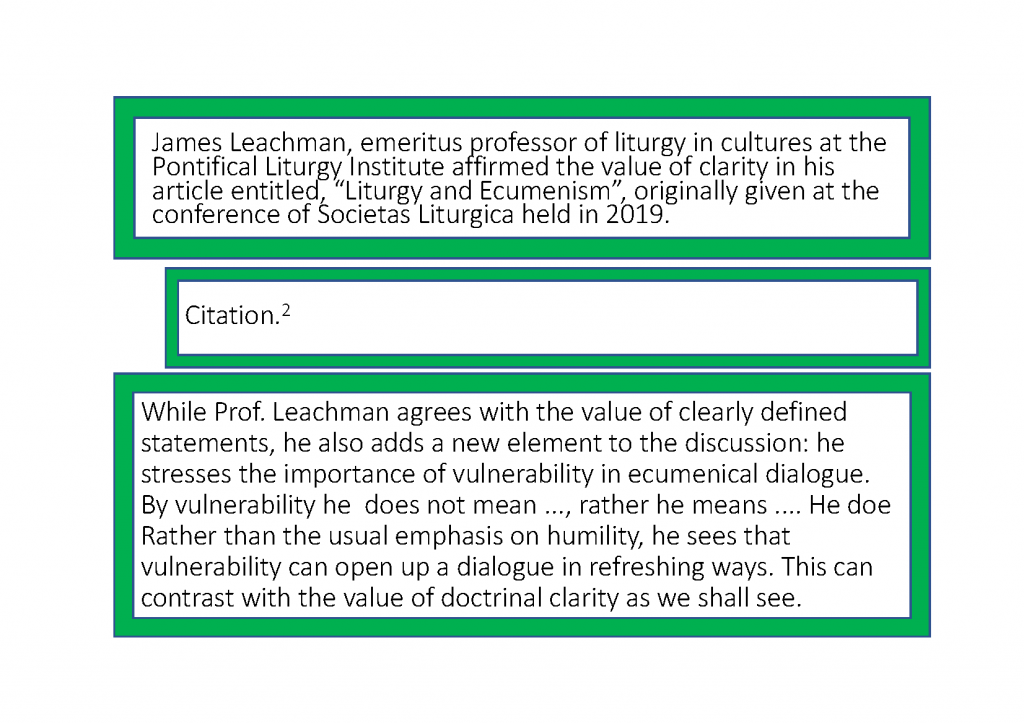

The following example indicates how to introduce and follow a citation, although the citation is not give here.

- The introductory paragraph identified the author as James Leachman and indicates his authority to speak about liturgy and ecumenism as a professor emeritus of liturgy and cultures at the PIL. We might imagine that the previous paragraph spoke about the value of clarity in ecumenical dialogue, because the writer next says that Prof. Leachman also values such clarity. Next the writer introduces the context in which Prof. Leachman gave the following statement, at a conference of Societas Liturgica, and the date is given as 2019.

- After the citation the author picks up once again the same concern for clarity in ecumenical dialogue, but then states the proper contribution that Prof. Leachman made in the cited paper. In addition to clarity, the author highlights the value Prof. Leachman places on vulnerability. In fact, when vulnerability enters into ecumenical dialogue, the discussion can be changed in “refreshing ways”.

This example makes it clear that the purpose of citing another person is not to let them talk for the writer, but to engage in a dialogue with another person. For this we must practice respect for the writing of another which in turn enhances the respect we give to our own contribution.

Indirect discourse

If the student would like to take the work of another author and summarise it in the student’s own words, or to present it in the student’s own words, then, the student is to introduce the original author and source at the beginning. In this case, according to my rule, no three words in a row may be used directly from the original text. Rather, now the student is expressing the ideas in the student’s own words. The student must still give a footnote citation to the text of the original author. Perhaps a few specific examples would be helpful.

While Prof. Leachman agrees with the value of clearly defined statements,

After the citation the author picks up once again the same concern for clarity in ecumenical dialogue,

The first statement is quoted from the green box above, and the second is my own restatement of the same text. it is rest. In restating the text I am also giving some of my own insight about the overall argument and its emphasis on clarity. Both statements then continue with the following.

he also adds a new element to the discussion:

but then states the proper contribution that Prof. Leachman made in the cited paper.

Both texts continue as follows.

he stresses the importance of vulnerability in ecumenical dialogue. By vulnerability he does not mean …, rather he means ….

In addition to clarity, the author highlights the value Prof. Leachman places on vulnerability.

I have simplified the first text above with two elipses: … . Both paragraphs conclude in the following way.

Rather than the usual emphasis on humility, he sees that vulnerability can open up a dialogue in refreshing ways. This can contrast with the value of doctrinal clarity as we shall see.

In fact, when vulnerability enters into ecumenical dialogue, the discussion can be changed in “refreshing ways”.

Finally, I quote the exact words used by Prof. Leachman because they are so appropriate, not because I could not have have said it in some other way.

My personal rule for indirect statements such as these is that if I use three words in a row from the original text I must put them in “double inverted commas”, and cite them in a footnote. Some other style guides allow five words in a row from the original text.

The clue to indirect statement is that the writer must consider the original text very well, and next consider the writer’s own thought process and argument, and only then can the writer tell the story in one’s own words, without relying directly upon the words of another.

Updated © 1 May 2020 Daniel P. McCarthy.