Collects is a study of the Latin expression and theological meaning of the proper prayer of the day from the Missale Romanum of 2008 sponsored by the:

PONTIFICAL LITURGY INSTITUTE

The Latin Expression and Theological Meaning

of Selected Collects

of the Lent and Easter seasons

from the Missale Romanum 2008

Taught by: Daniel McCarthy

Course offered in English: 94208 (3 ECTS)

This page is currently being revised for the Spring semester 2021.

Go to each stage in the the literary analyais of a collect type prayer.

write out the text and read it

prayer texts align on the left side only

Box words going together { [ ( < > ) ] }

Draw a tree

Draw the timeline of the actions of the prayer

Discern the interpretative categories of the prayer

Arrange the interpretative categories of the prayer

Writing a commentary on your prayer

Who does what to whom?

Who does what?

Who does what to whom?

Maping human maturation

Anamnesis in collects

Epiclesis in collects

Eschatology in collects

Theosis in collects

Brief description

This course comprises a detailed study of selected collects of the Lent and Easter seasons from the Missale Romanum using the methodology of the Pontifical Liturgical Institute. The Latin expression, structure and dynamic of the collects will be made clear and four pairs of interpretative keys will be used to appreciate the meaning of the collects in their liturgical-ritual context. Students will grow in their ability and confidence to understand the Latin texts of these prayers and render them into standard English, and to discuss their theological meaning.

Aims

By the end of the course the student will be able:

- to follow a method presented in understanding and interpreting a different collect during each session,

- to apply the given method to one named Latin collect, accounting for its Latin expression, and rendering it into standard English,

- to explain the principles behind the four pairs of interpretative keys:

anamnesis (narration – ritual programme);

epiclesis (presentation – invocation);

eschatology – (fulfillment – moral life and personal maturation).

theosis (a personal way of living in freedom and love). - to interpret the named Latin collect in its liturgical-ritual context according to these four pairs of interpretative keys

Structure of the course

During each session we shall follow a determined method in examining together a collect. New elements of this method will be presented each session according to two major areas:

First, the Latin expression of the collect will be considered to understand the function of each word in the sentence and the literary structure of the collect, its timeline of events, the interpretative categories of its clauses and its presentation of the divine human exchange.

Second, the interpretation of the collect begins with an understanding of its liturgical-ritual context and continues with an application of the four pairs of interpretative keys to distern their expression in the collect

Learning activities

- The instructor will present the elements of the method gradually each session, beginning first with an analysis of the Latin text and literary structure of the prayer, and then continuing with the interpretation of the prayer’s liturgical-ritual context and the four pairs of interpretative keys.

- A student will be asked to assist in the presentation of each collect guided by the instructor, and all students will participate in applying gradually more elements of this method to a different collect each session.

- At the beginning of the course each student will select an agreed upon collect from the Missale Romanum. As each element of the method is presented, the student will apply it to the named collect during private study

Schedule 2021

The course is scheduled for Tuesday afternoons of the Spring semester 2021. Sessions begin at 15:30 on each of the following days:

February 16, 23,

March 2, 9, 16, 23.

Hours: 14:30-17:50

First session: 14:30-15:15

Break: 15:15-15:20

Second session: 15:20-16:05

Break: 16:05-16:15

Third session: 16:15-17:00

Break: 17:00-17:05

Fourth session: 17:05-17:50

Office Hours

Please do not phone the instructor. Rather email him at daniel AT anselmianum DOT com.

He is available outside of class time by appointment.

Bibliography

♦ Latin-English dictionary such as D.P. SIMPSON, Cassell’s English Dictionary, New York-Oxford 1968; or C.T. LEWIS – C. SHORT, A Latin Dictionary, Oxford UP, Oxford – New York 1879 (or later reprint).

♦ Appreciating the Collect: An Irenic Methodology, ed. J.G. Leachman – D.P. McCarthy (Documenta rerum ecclesiasticarum instaurata, Liturgiam aestimare: Appreciating the Liturgy 1), St. Michael’s Abbey Press, Farnborough 2008.

♦ MCCARTHY, D.P. – J.G. LEACHMAN, Listen to the Word: Commentaries on Selected Opening Prayers of Sundays and Feasts, The Tablet, London 2009.

♦ FOSTER, R. – D.P. MCCARTHY, Ossa Latinitatis Sola ad mentem Reginaldi rationemque: The mere bones of Latin according to the thought and system of Reginald (Latinitatis Corpus 1), Catholic University of America Press, Washington DC

also recommended:

♦ Transition in the Easter Vigil: Becoming Christians. Paschali in vigilia Christiani nominis fieri, ed. D.P. McCarthy – J.G. Leachman (Documenta rerum ecclesiasticarum instaurata, Liturgiam aestimare: Appreciating the Liturgy 2), St. Michael’s Abbey Press, Farnborough 2011.

♦ McCARTHY, D.P. – J.G. LEACHMAN – R.T. FOSTER, Companion to the Missal: Reprints from The Tablet of London. Originally published from 18 March 2006 to 26 November 2011 (Documenta rerum ecclesiasticarum instaurata, Liturgiam aestimare: Appreciating the Liturgy, Varia), privately published in collaboration with the Library officials of the Pontificium Athenaeum Sancti Anselmi de Urbe, Roma 2019.

♦ MCCARTHY, D., “Seeing a Reflection, Considering Appearances: The History, Theology and Literary Composition of the Missale Romanum at a Time of Vernacular Reflection”, Questions Liturgiques / Studies in Liturgy 94 (2013) 109-143.

♦ LEACHMAN, J.G., – D.P. MCCARTHY, “A Liturgical Study of the proper prayers for St Charles of St Andrew Houben, C.P., (1) The Opening Prayer,” Questions Liturgiques: Studies in Liturgy 92 (2011) 28-44 (second edition of “J.G. Leachman, “Studium liturgiczne kolekty o św. Karolu od św. Andrzeja Houbenie CP”, Słowo Krzyża Crucis Verbum 4 [2010], 230-243).

♦ RUSSELL, N., The Doctrine of Deification in the Greek Patristic Tradition (Oxford Early Christian Studies), Oxford UP, Oxford 2006.

♦ REGAN, P., “The Collect in Context”, in Appreciating the Collect, ed. Leachman, St. Michael’s Abbey Press, Farnborough 2008.

♦ Latin Work Study Tool with the Lewis and Short dictionary available here: Enter an inflected form of your word in the field under the heading “Dictionary Entry Lookup”, located in the column on the right.

♦ LEWIS and SHORT dictionary available here: Enter the dictionary entry for your word in the field under the heading “Dictionary Entry Lookup”, located in the column on the right.

♦ Logeion

Even more Latin dictionaries are available on Logeion, including Lewis and Short. Enter the dictionary entry for your word in the field at the top of this page. If the search produces entries from several different dictionaries, they are listed first and you can choose which one you wish to consult.

Examination

Preparation: At the beginning of the course the student select one of the prayers that we shall consider during this course. As we progress through each step of analysis and interpretation, the student applies each to the chosen prayer. For the exam the student is to have a thorough knowledge of the Latin expression of the prayer and be able to explain the function of each word in the prayer if needed. Such knowledge, however, is foundational to the discussion during the oral exam. The student is to prepare an interpretation of the chosen prayer according to all four interpretative keys.

Explanation: During the oral exam the instructor chooses one of the four interpretative keys. The student both demonstrates an understanding of the theory involved in the chosen interpretative key and then applies the interpretative key to the selected collect in its liturgical-ritual context. Only if there is doubt, will the instructor ask the student about the function of any Latin word of the collect and its literary composition.

Criteria for evaluation: Both the regular participation of the student in class discussions and a final oral exam are assessed based on the following criteria:

- a clear understanding of the function of each word and the literary structure of the Latin collect,

- a clearly developed presentation of the selected interpretative key,

- a well considered application of the selected interpretative key to the text of the collect in its liturgical-ritual context.

This is an open book exam, so students may bring their notes and printed resources. The exam is timed, so the student is advised to prepare the material well and then to focus on the essential elements for presentation. The instructor may ask questions to help the student provide a fuller response.

Academic program

The program of studies, course descriptions and calendar for the academic year 2020-2021 is available for download here.

Place

This course is offered in English at the Pontifical Institute of Liturgy housed at:

Sant’Anselmo

Piazza Cavalieri di Malta, 5

00153 Roma, Italia

See map below.

Collects of Sundays in Lent and of Easter

Note well: Students are encouraged to download and print this document which contains the collects of the Sundays and Feasts of Lent and Easter, which we shall coinsider from the Missale Romanum 2008. Please bring this document to each class encounter so that you may use it to take notes on the prayers as they are presented. If the order of prayers is changed without notification, you will have the text already in hand and will not have to take class time to write out the text in longhand.

Students are also requested to print this web-page which contains the course description and the class schedule and bring this print-out to each session so that the student will have all of the resources necessary for our discussions.

Each student is encouraged to access the instructor’s English translations of numerous mass formularies of Sundays and feasts published in The Tablet of London from 28 November 2009 – 20 November 2010, available on the reserve shelf in the library.

A listing of these commentaries arranged according to their liturgical day is found at this link. In the entry for each liturgical day, following the heading “Collecta”, you will find bibliographical entry for my article on the collect of that liturgical day. However, my published translations of most of these very same collects is found in the article given after the heading “Study translation of the four prayers”. In this way you will be able to use and reference my published translation of the prayer you have already chosen. My commentaries on the collects were slightly revised for publication in the volume Listen to the Word in the S’A library at: Lit 3727a. All of the original commentaries and translations are found in the privately published volume Companion to the Missal also in the S’A library at: Lit 3727b. Many of these volumes should be found in the library on a shelf reserved for my classes and seminars.

Schedule in detail

I have adjusted the learning activities of this course for academic year 2020-2021. We shall have a handful of students new to this method of analysis and interpretation of prayers and we shall have a handful of students who are writing their license tesina or doctoral tesi on prayer texts.

Those new to this method are asked to choose a collect prayer from a Sunday or Feast day of the Lenten or Easter season, according to the list available here.

Those writing their tesina or tesi are interested in reviewing the four interpretative keys both for their theory and for their application to their prayers. I have also asked them to give a guiding hand to those people new to these methods of analysis and interpretation.

As a result, I shall ask the more advanced to present first the Latin expression of one or more prayers they are working on, as a way of teaching people new to this method.

In response those new to this method will present their analysis of the Latin structure of their chosen prayers. Before presenting, however, they are requested to submit their draft to the instructor for his review and correction if needed before the classroom presentation.

Next, the instructor will present the theory of the four interpretative keys, each in a different session. Those more advanced will illustrate each key by showing how their key characterises their chosen prayer.

Those new to the process will also have the opportunity to present their interpretations of their prayers according to the four interpretative keys.

Session 1: 16 February 2021

We shall meet one another.

The instructor will introduce the course, and explain the method of exam.

We shall begin our method of understanding of the Latin composition of a prayer using the following Questions for the literary analysis of a prayer.

Questions for the literary analysis of a prayer:

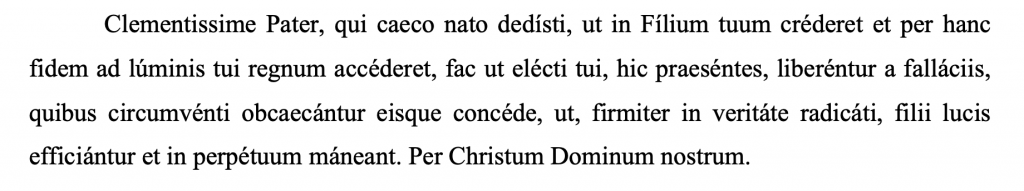

Write out the text and read it

- Write out the prayer.

- Write out the prayer as it appears in the liturgical books.

- This means that the prayer is broken up into sense lines so that the words on each line of text belong together – it does no good to write the prayer as one sentence of prose text. Examples are given below.

- If you are printing the text on paper, leave double spacing or more between each line of text so that there is room to make notes.

- If your computer automatically corrects the Latin text or capitalises the first word of each line, please correct these – these are your responsibility. You might turn off “auto-correct” on your computer.

- You may include the accent marks to help people read the prayer aloud.

- Above the prayer write out the heading that the prayer appears under in the liturgical book so that we may have an idea of its context.

- Read outloud the prayer.

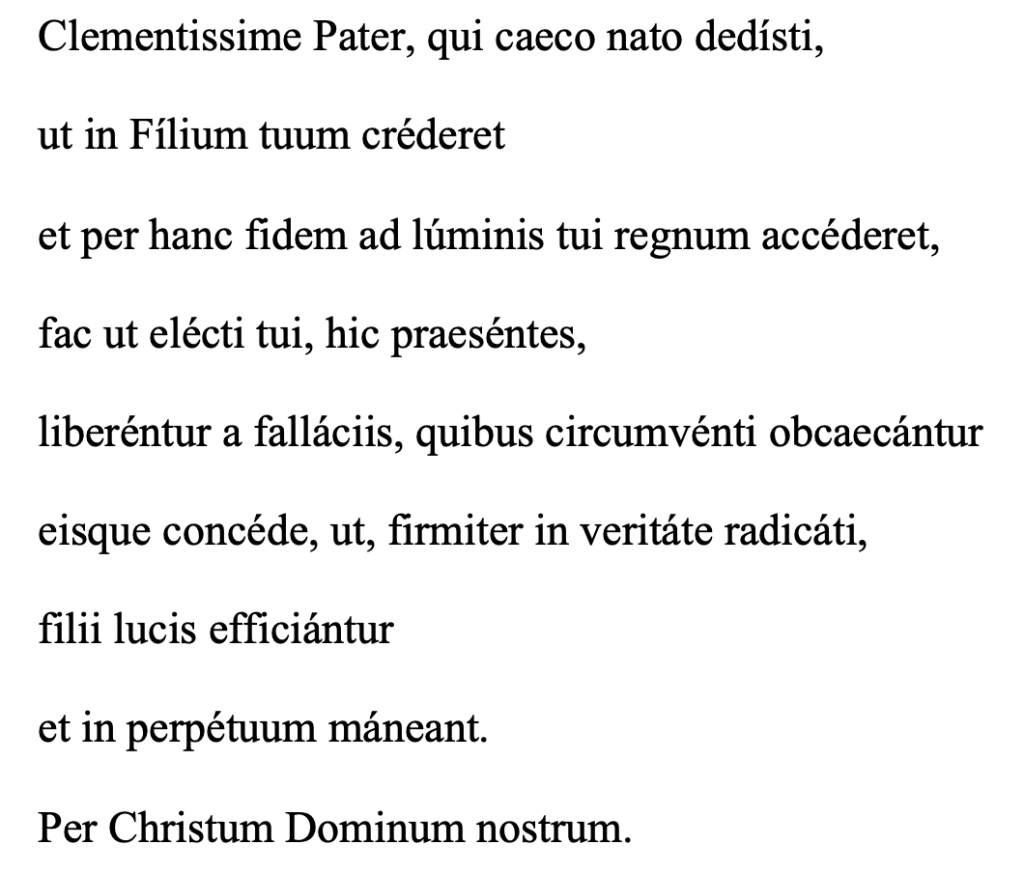

Prayer texts align on the left side only

Do not write out your prayer like the following paragraph.

A prayer is not like a paragraph in a novel.

Write out your prayer as it appears in current liturgical books like the following prayer. You an see the meaning of words more easily, if each line has words which go together. This is more like poetry.

You can find instructions for aligning text on the left side only or on both sides using Word such as these.

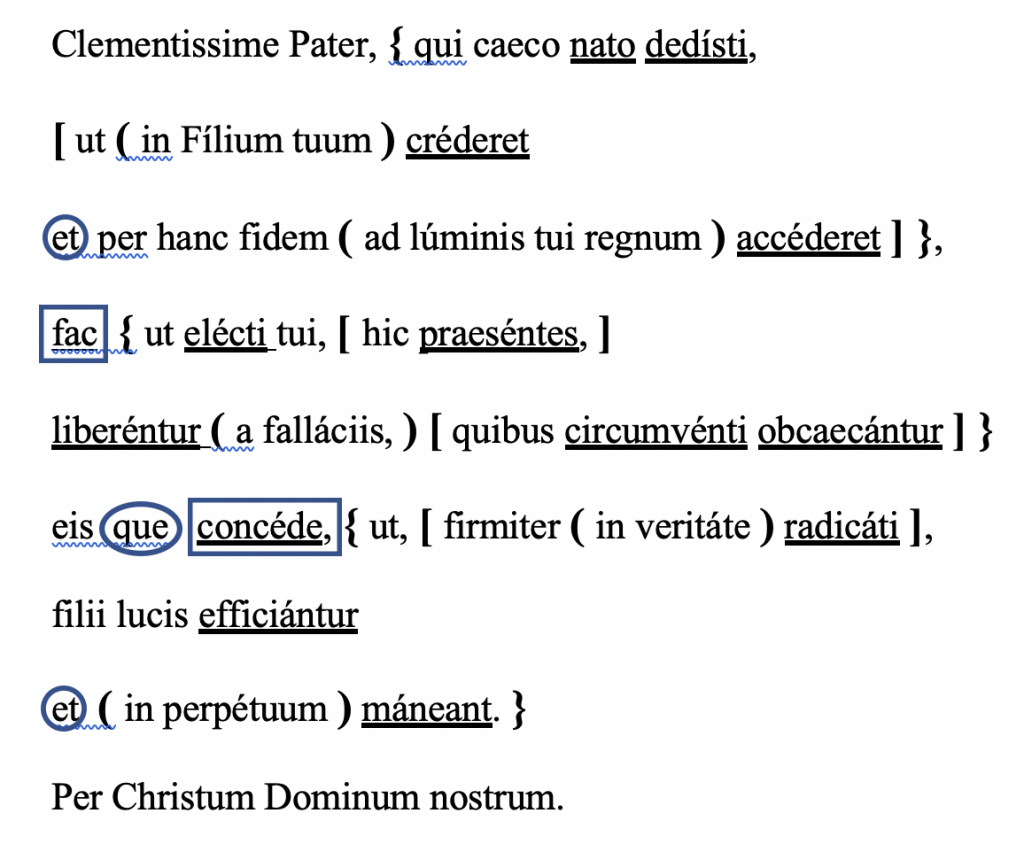

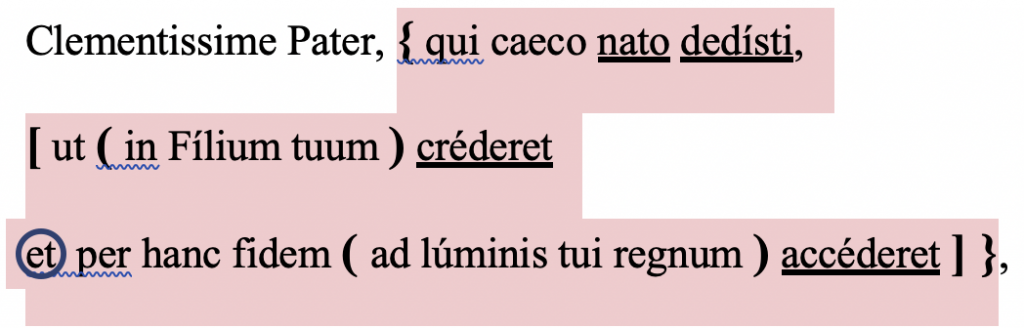

Box words going together { [ ( < > ) ] }

- Underline the action words (verbs, participles, gerunds, gerundives).

- Put a box around the main, independent, finite verb of the sentence.

- Put circles around connecting words such as et, -que, sicut etc. Identify the words they connect.

- The relative pronoun opens a clause. Put an open square bracket before the relative pronoun: “ [ ”. Then answer these two questions in the following order:

- Where is its verb?

- Where does the clause end? Mark its end with a close square bracket: “ ] ”. (See: Ossa, Encounters 10-11, 23, 28, 33)

- Name the antecedent of the relative pronoun.

- Remember the function of the relative pronoun comes from whithin its own clause. It functions either as:

- subject (qui, quae, quod) = nomimnative,

- object (quem, quod, quos, quas, quae) = accusative,

- of-possession (cuius, quorum, quarum) = genitive,

- to-for-from (cui, quibus) = dative,

- by-with-from-in (quo, qua, quibus).

- The gender and number of the relative pronoun come from its antecedent usually located or implied outside its own clause.

- Remember the function of the relative pronoun comes from whithin its own clause. It functions either as:

- The ut opens a clause. Put an open fancy bracket “ { ” before the ut. Then answer these two questions in the following order:

- Where is its verb?

- Where does the clause end? Mark its end with a close fancy bracket: “ } ”. (See: Ossa, Encounters 58, 84)

- Note the fourteen ways to express purpose given in Ossa, Encounter 84.

- Put [ square brackets ] around participial clauses. The only four participle possibilities in Latin are:

- contemporaneous, active participle,

- antecedent (past), passive (note: deponent verbs have an antecedent active) participle,

- futurity, active participle,

- participle of passive necessity (See: Ossa, Encounters 50-53, 84).

- Identify any ablative absolute and mark it with [ square brackets ].

- Identify the subject given in the ablative form.

- Give the full, natural meaning of the participle with its subject in English, noting the time of the participle.

- Decide what relationship of the ablative absolute has to the rest of its sentence:

- when, after = temporal (this is the lightest touch and thus used most frequently),

- because, since = causal,

- although = concessive.

- The ablative absolute can function in just about any way in relation to the main sentence. (See: Ossa, Encounters 54-57)

- Where there is an infinitive, determine:

- Identify the time of the infinitive:

- contemporaneous active / passive infinitive,

- antecedent (before) active / passive infinitive,

- futurity active / passive infinitive.

- Identify how the infinitive functions in its sentence and the verb it depends upon.

- The infinitive may function as the subject or object of another verb (and thus functions as a gerund); (See: Ossa, Encounters 77)

- The infinitive may function as part of an accusative with the infinitive (indirect discourse) (See: Ossa, Encounters 71-73).

- Identify the subject of the infinitive which is given in the object (accusative) form.

- Identify the verb of M&M which gives rise to the sentence in the accusative with the infinitive.

- Give the three possible ways to express the accusative with the infinitive in English, namely:

- The English accusative with the infinitive.

- Supply the word “that”, then make the accusative subject a regular subject and make the infinitive a finite verb – be careful of the times of the infinitives and finite verbs.

- Replicate the above, without the word “that”.

- Note that sometimes a subject is given in an accusative form, but its infinitive is only implied.

- Identify the time of the infinitive:

- Is there a cum clause?

- Does cum function as a preposition followed by an object in the ablative?

- Is cum followed by a verb in the indicitave or subjunctive?

- Cum with all times of the indicative means “when”.

- Cum with all times of the subjunctive means either:

- because, since = causal,

- although = concessive.

- On Track II (historical sequence of tenses):

- Cum with the indicative means “when” as in clock-time coincidence

- Cum with the subjunctive can mean “when” giving a temporal circumstance and almost means “because”.

- Other forms of causal clauses meaning “because” may begin with:

- quod, quia, quoniam:

- followed by the indicative to give the author’s own idea,

- followed by the subjunctive to give the idea of another, a reported idea;

- Quando, quandoquidem (followed by the indicative), siquidem;

- qui, quae, quod followed by the subjunctive;

- quippe qui, utpote qui followed by the subjunctive (see: Ossa, Encounter 59.3).

- quod, quia, quoniam:

- Identify the prepositions and their objects (accusative or ablative). Put ( rounded parentheses ) around prepositional phrases. (See: Ossa, Encounters 6, 28)

- Writing a paper on your prayer: First make sure that the boxes are correctly drawn and labeled with the agreement of the moderator, before moving on to the next step: drawing a tree.

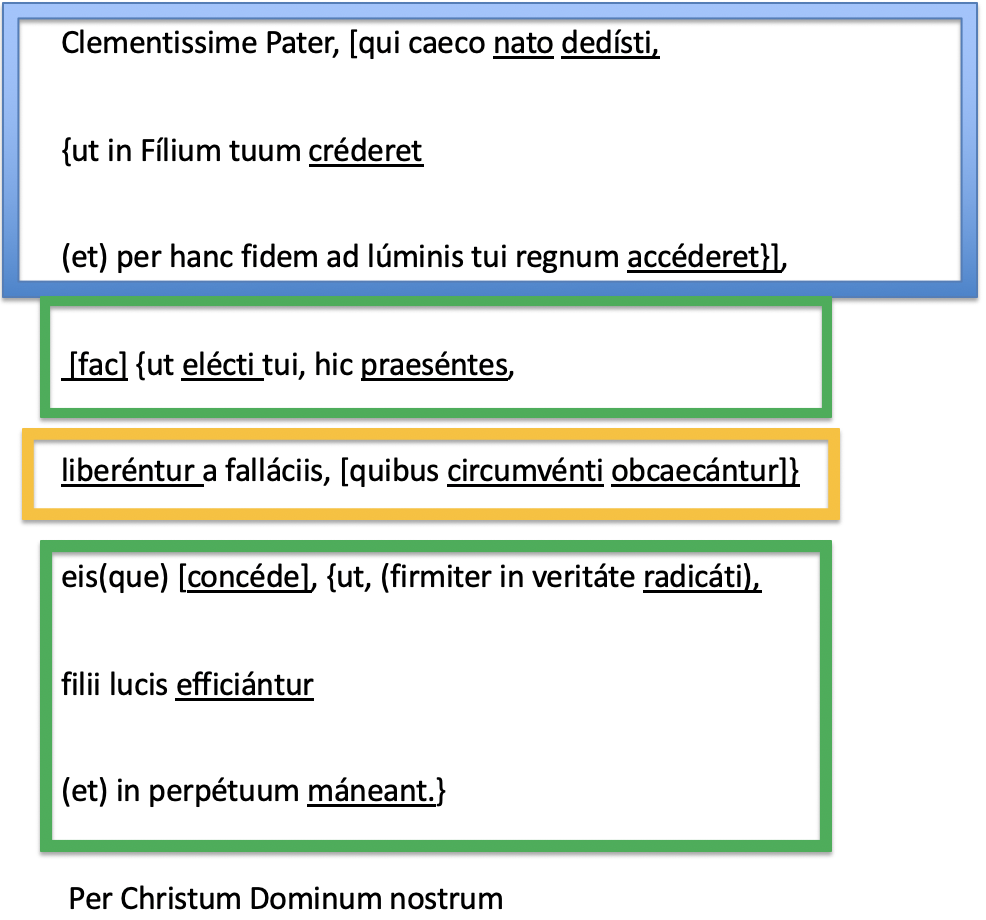

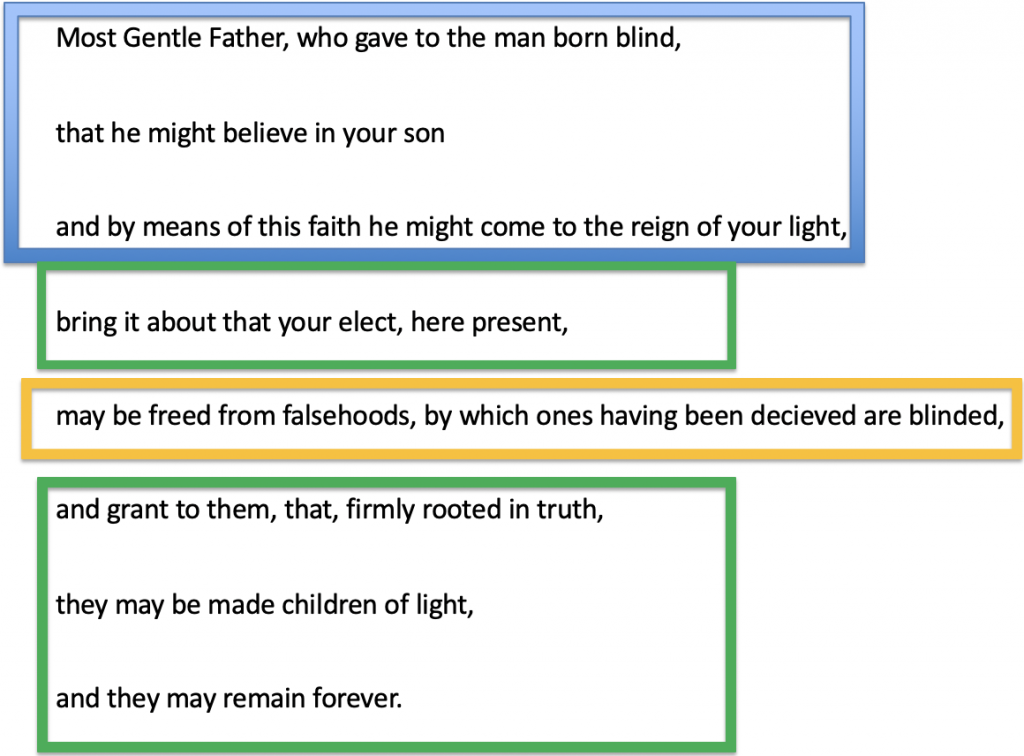

Your boxes and brackets should look something like the following image when you are done. Each bracket includes words which go together

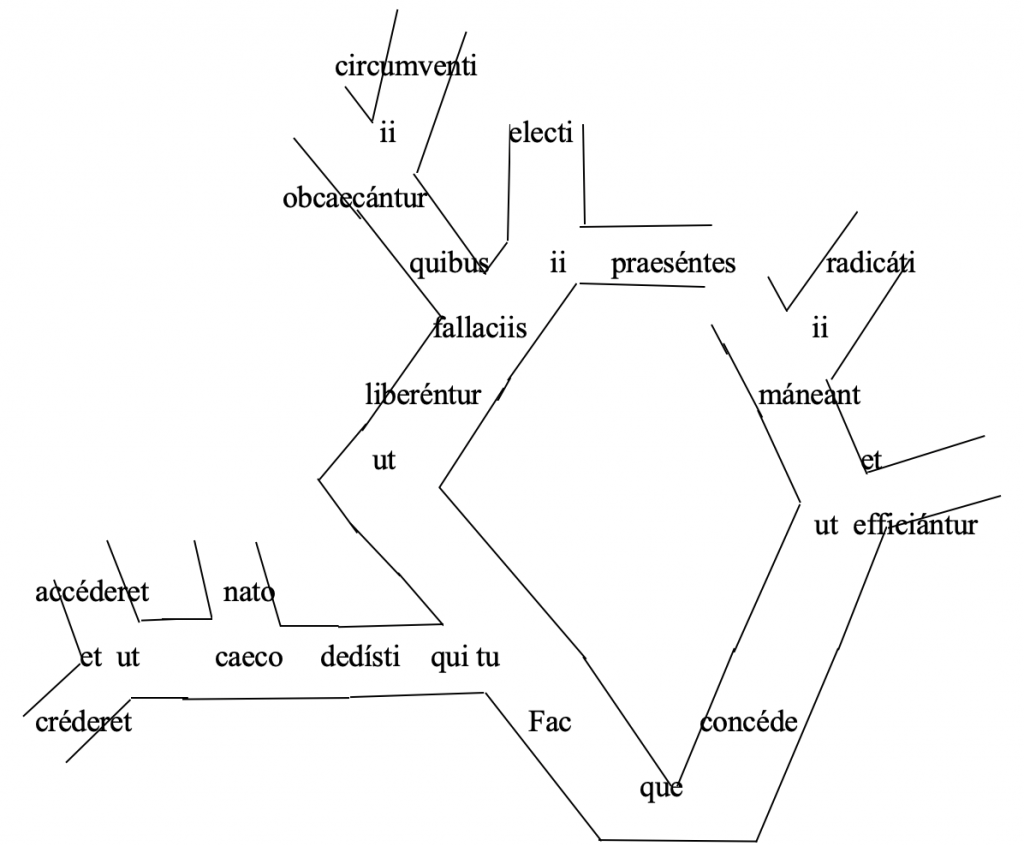

Draw a tree

- Draw a tree showing the dependencies of the clauses.

- Note that the tree is a graphic way of representing the brackets you have already drawn and the dependency of one clause upon another (see: Ossa, Encounter 11.4 on the box effect).

- The main verb goes in the trunk of the tree.

- Each clause in brackets, depending directly on the main verb, forms a branch comming off of the main trunk.

- Within these main brackets, each smaller clause is drawn as a branch coming off the clause it stands within and depends upon.

- When drawing each branch:

- Write the verbal form on the branch itself.

- At the place where the branch joins the rest of the tree give the connecting word such as a relative pronoun qui, quae, quod …, or such as ut, cum, or coordinating particles such as sicut.

- If this connnecting word is a relative pronoun, name the antecedent on the main branch. If it is not expressed, then give it as a pronoun such as: is, ea, id, eius, ei, eo, ea, eum, eam, ii (ei), eae, ibus, eos, eas.

- Where the connecting word is a correlative particle such as sicut, give the other part of the correlative in its proper place.

Most people know what a tree looks like, yet there are so many different ways of drawing trees. Drawing a tree on a computer poses its own problems. Here is an abstract tree. Note that each action word has a branch, and the joints are labeled with the words which join the different actions.

- Establish the times of verbs and their several possible English equivalents (see: Ossa, Encounters 7)

- Draw a timeline of the actions and goals (see: Ossa, Encounters 44)

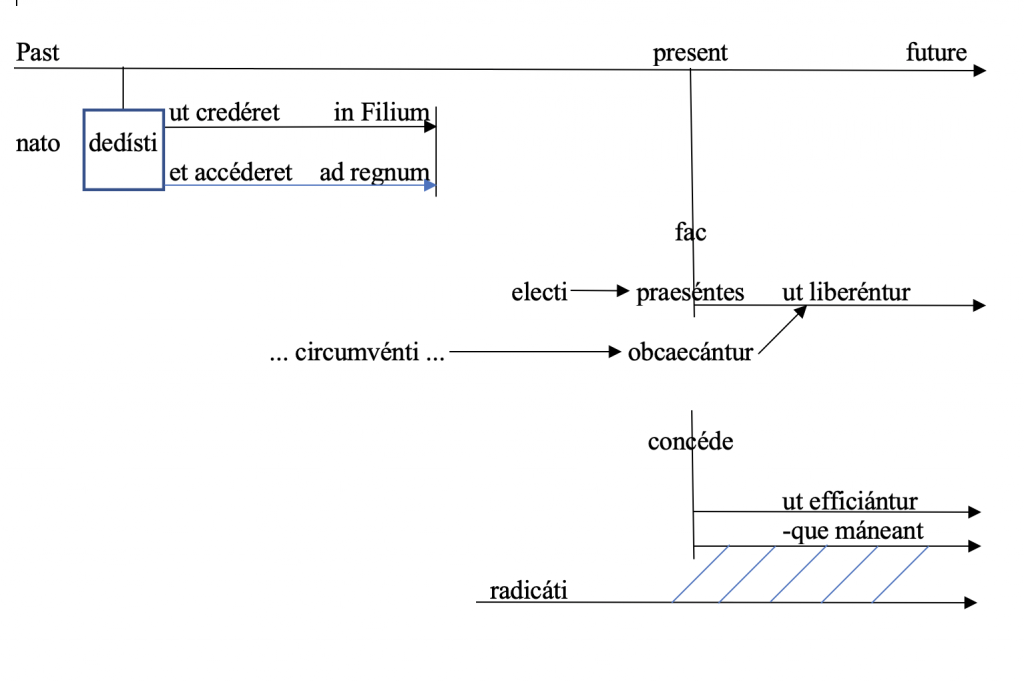

Draw the timeline of the actions of the prayer

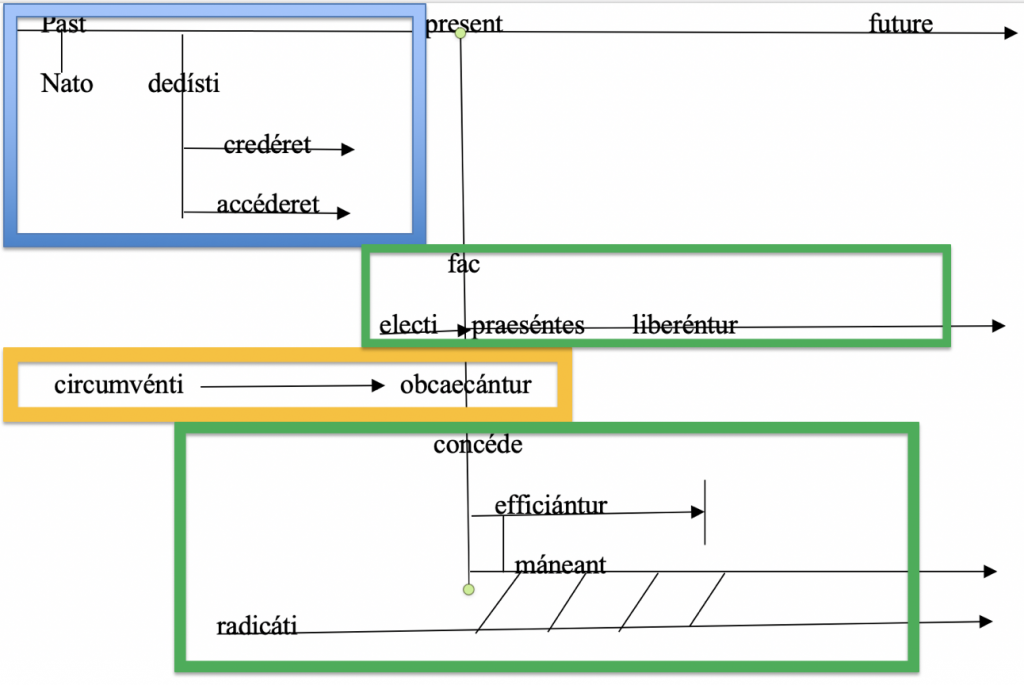

The following is a well developed timeline. You must begin with the main verbs, and then work your way out each branch of the tree one action at a time. In this way the time line shows the dependence of one action upon another. Then you must show the times of participles and subordinate subjunctive verbs along with other subordinate verbal forms relative to the actions they each depend upon. Participles and subjunctive forms may have time which extend over time, others not.

- Begin with the top horizontal arrow which stretches from the past into the future.

- In the present place a vertical line.

- Begin with the independent verb or verbs. Here there are two fac and concede, so in a sense there are two distinct timelines. That is why I have drawn a break in the vertical line centered on the present.

- Depending on fac there is both a relative clause which occupies the top left part of this timeline.

- Verbs in T.4bi are indicated with a square box around them, because they present a photographic picture of an action at one point in time in the past. This is viewed from the present as a completed historical event.

- Verbs in T.4ai are indicated with a square box around them, because they present a photographic picture of an action at one point in time in the past, and an arrow extends from that square box to the present moment because these verbs are viewed from the present as historical events touching on the presetn. This chart does not have any of these.

- The participle nato occurrs before dedisti, and so stands on its own out to the left. In this case nato does not have an arrow leading to dedisti because the birth of the man is considered to be the equivalent as a verb in T.4bi, that is as an historical event set in the past and not touching on the time of dedisti.

- The verb dedisti produces a double purpose clause. Relative to the time of the action of dedisti upon which they depend, the full, natural time frame of both crederet and accederet is ongoing, unfinished, in process, incomplete, future, eternal and contemporaneous (see Ossa p. 309, T.2s in the chart). That is why the arrows begin at the box for dedisti and extend into the future. The full, natural time of these two subjunctive verbs in this case does not stretch to eternity. According to the gospel account the man born blind came to profess his faith in Jesus and so approach … . Thus these two arrows end at the point when the man born blind comes to believe and approach … .

- The last paragraph ends with three dots, because there is something more to the account in the prayer. Both of these subjunctive verbs lead to goals expressed by either in or ad and the object form, which indicates here moral motion toward a goal. Here the goals are believing in Filium and approaching ad regnum. The goal is represented by a short vertical line set at the historical point when the man born blind came to believe and approach. The movement toward these goals is indicated by the arrows. The words expressing these goals are aligned to the right side so that they bump up against the vertical line of the goal.

- The main verb fac produces a purpose clause expressing the divine intention for which the church prays.

- This purpose clause is expressed by ut … liberentur. Relative to the time of the action of fac upon which it depends, the full, natural time frame of liberentur is ongoing, unfinished, in process, incomplete, future, eternal and contemporaneous (see Ossa p. 309, T.1s in the chart). This is drawn by an arrow which begins at the vertical line of the present, that is at the time of fac, and continues into the future. There is no goal expressed here, so the arrow continues presumably into eternity according to the full natural time frame of liberentur depending on fac.

- We have discerned that praesentes is almost paranthetically set into the purpose clause. Its time is in the present, so it is centered on the vertical line.

- The participle electi describes an action completed prior to praesentes. In the OICA the rite of election normally occurs on the first Sunday of Lent, so the participle electi is placed at that moment in the timeline. The rite of election, however, is not viewed as an historical event completed in the past, but as an historical event touching on the present, as an equivalent of a verb in T.4ai, and so it has an arrow which extends to the time of praesentes.

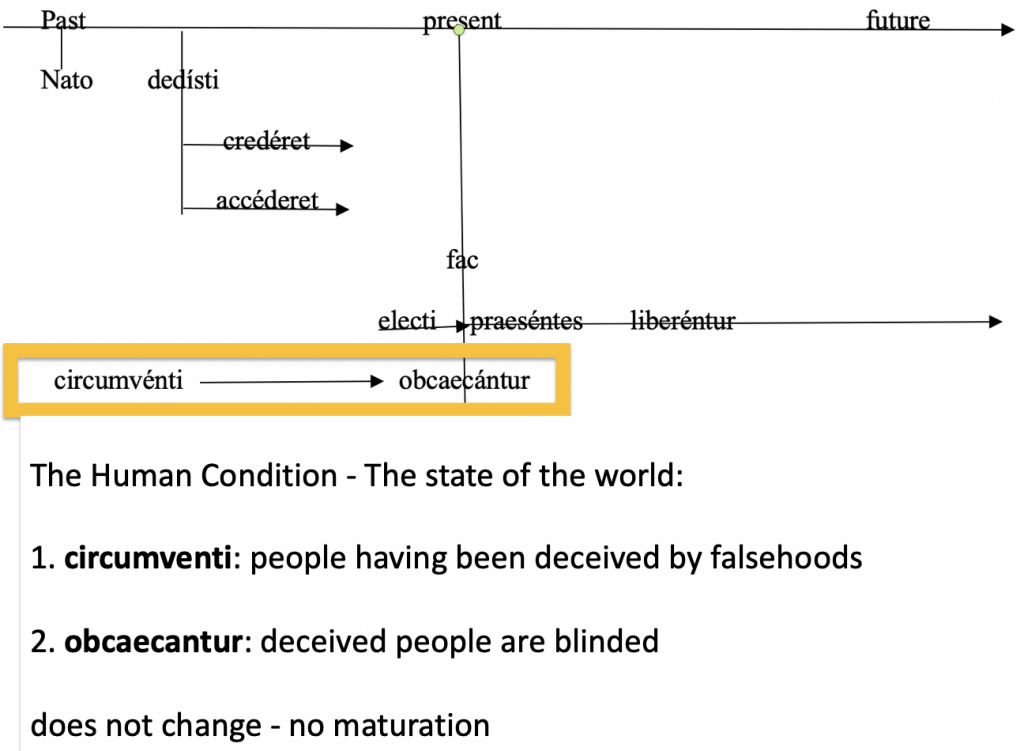

- The purpose clause has a relative clause nestled within it. Its verb is obcaecantur which is also set in the present. Note that obcaecantur is placed in the present moment, but the vertical line marking the present moment does not pass through this verb. This is because this verb does not depend directly upon fac. Rather obcaecantur depends upon liberentur which depends upon fac. Thus, an arrow was drawn at an antle from obcaencatur to liberentur to indicate that people who are blinded in the present may be liberated. The other option is to take obcaecantur as parenthetically set into the purpose clause like praesentes above.

- The participle circumventi which both depends upon and occurs before the time of obcaecantur. We have taken circumventi as the equivalent of a verb in T.4ai, that is as a past event touching on the present. The people are blind now because they have been deceived previously. So we have drawn an arrow from circumventi to obcaecantur to represent this time frame.

- We set circumventi at some indescript moment in the past in order to advoid the impression that circumventi occurs at the same time as electi. There is no reason to assume they occur at the same time, so to advoid this impression we have located circumventi at an earlier time and placed … before and … after the verb.

- You can see that the timeline indicates both the dependency of one verb upon another and the time of one action relative to other actions.

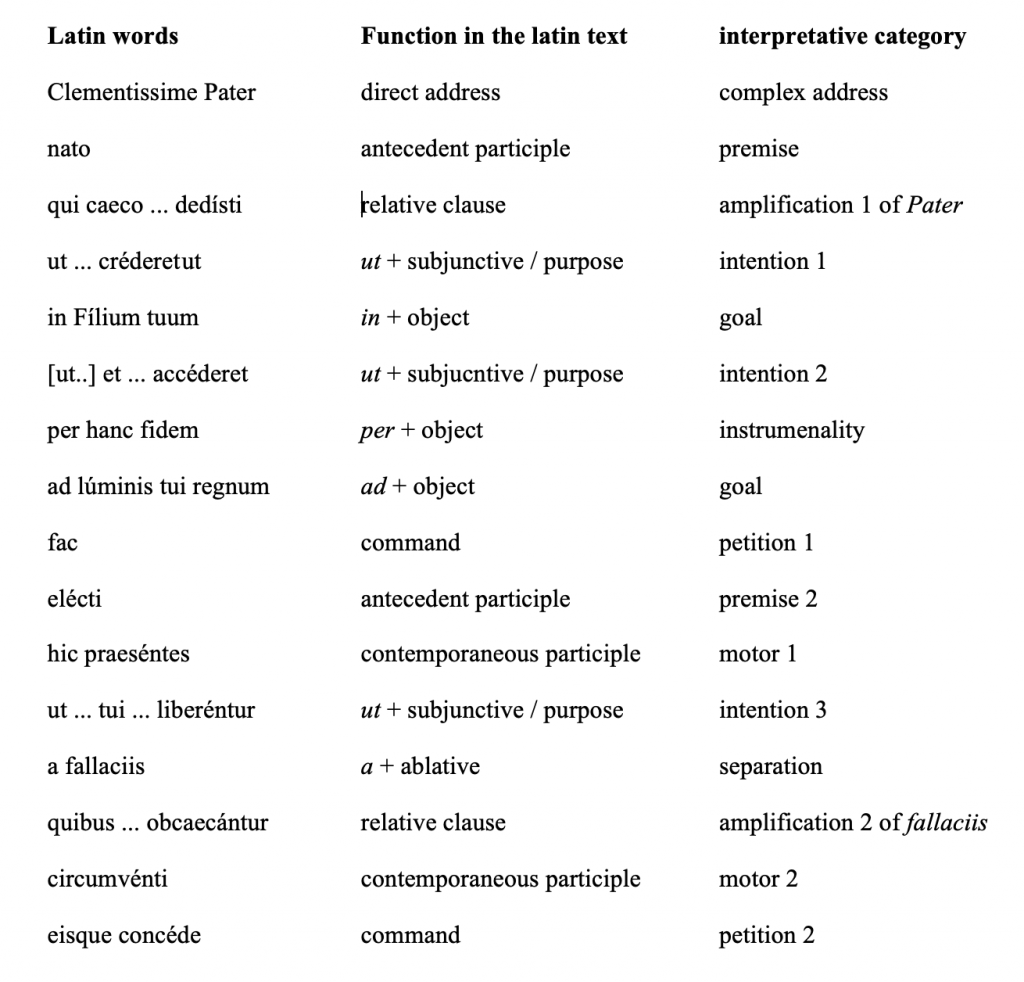

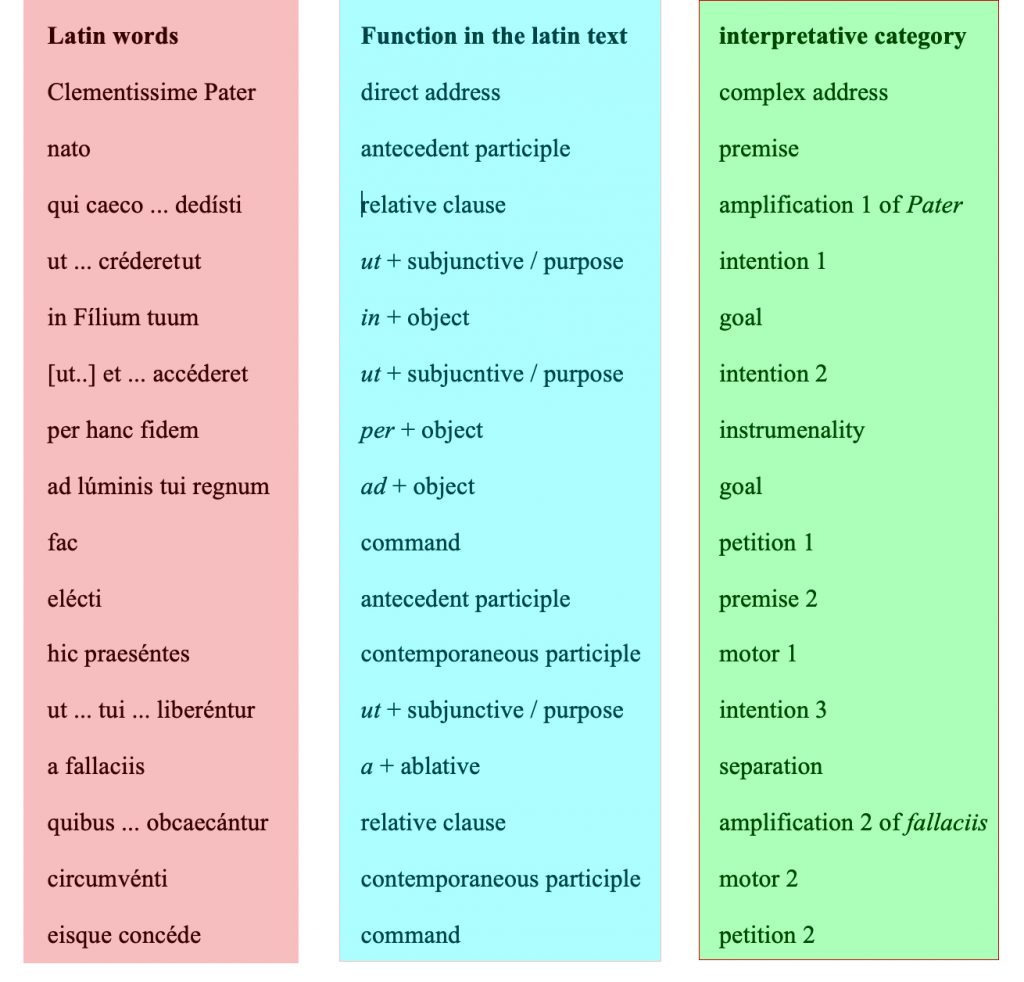

Discern the interpretative categories of the prayer

- Draw a box with three columns.

- In the column on the left write each word of the Latin text one clause at a time.

- In the middle column give the function of the clause in the Latin sentence (its grammatical term given in italic script below).

- In the column to the right assign the interpretative category (see De Zan). These include:

- Address expressed as direct address (see: Ossa, Encounter 38.3);

- Amplification given as:

- A relative clause (see: Ossa, Encounters 10-11),

- A noun or adjective in apposition (this means that a noun or adjective is butted up against another word, without a connecting word such as, “O God, just Judge, who …” where “just Judge” are placed next to the direct address without any connecting word);

- Petition given as:

- A first or second command (see: Ossa, Encounters 17, 34, 85),

- An independent verb in the subjunctive (see: Ossa, Encounters 94.3);

- Motor driving the prayer to its conclusion given as:

- A participial phrase, active or passive (see: Ossa, Encounters 50-53),

- A relative clause (see: Ossa, Encounters 10-11),

- An ablative absolute (see: Ossa, Encounters 54-57),

- Note that what I call “motor”, Prof. De Zan calls “motive”;

- Purpose

- Expressed in one of 14 ways (see: Ossa, Encounter 84),

- Given as an accusative with the infinitive (see: Ossa, Encounters 71-73);

- Premise (presumed context for the prayer) expressed as:

- Given as an accusative with the infinitive (see: Ossa, Encounters 71-73),

- An ablative absolute (see: Ossa, Encounters 54-57);

- Goal (in or ad + object) (see: Ossa, Encounter 6).

- On interpretative categories see: 1) R. De Zan, “How to Interpret a Collect”, Appreciating the Collect, 6.3 on p. 75;

2) D.P. McCarthy, “Between Memories and Hopes: Anamnesis and Eschatology in selected collects”, Appreciating the Collect;

3) Listen to the Word – many examples of using this method.

4) Transition in the Easter vigil – many examples of using this method.

- Note that several grammatical categories such as the ablative absolute and the accusative with the infinitive may function in different ways, so a degree of interpretatnion needed in assigning the interpretative categories. The question is how the clause functions in the overall sentence in moving the thought forward.

Arrange the interpretative categories of the prayer

This clause in our sample prayer suggests some difficulties for arranging each clause in its order.

- cont.

- Finally, consider the order in which you arrange the entries of this chart.

- Generally each clause is treated in the order in which it comes.

- But there is a problem in this prayer because some clauses have other clauses nestled within them, so which clause is placed first in the chart? For example, the shaded text in the image above shows:

- a relative clause, qui … .

- This relative clause includes an antecedent preposition nato.

- Depending on this relative clause is a purpose clause ut … .

- Within this purpose clause there are three prepositional clauses

- in … and

- ad …

- and without brackets per … .

- In which order are you going to place these in a sequential chart?

- In the chart further below I ordered the items according to this rationale:

- The address appears first in the prayer

- The premise nato states the context for the relative clause, the man had long ago been born blind, so I placed it before the relative clause.

- Next comes the relative caluse.

- Notice that in the place where the participle nato belongs, I placed a space followed by three dots and a final space. This is called an elipsis. It serves as a place holder for words which I have removed.

- The purpose clause depends upon the relative clause, so it comes next.

- But the purpose clause has several parts. First there is an intention ut … crederet and a goal in Filium. Because the intention leads to the goal, and the goal is the end of the movement of this grouping, I placed the intention first and the goal next.

- Next there is another intention, with an expression of instrumentality and another goal. Again, I figure that the intention [ut] et … accederet leads to the goal. But I placed the instrument between the two to indicate the means for attaining that goal. Thus first I placed [ut] et … accederet and next the instrument per … and finally the goal ad … .

- Finally we arrive at fac the independent, finite verb, the command form or petition upon which the entire first half of this prayer depends.

- Finally, consider the order in which you arrange the entries of this chart.

The following is an example of how part of one extended prayer is assigned interpretative categories.

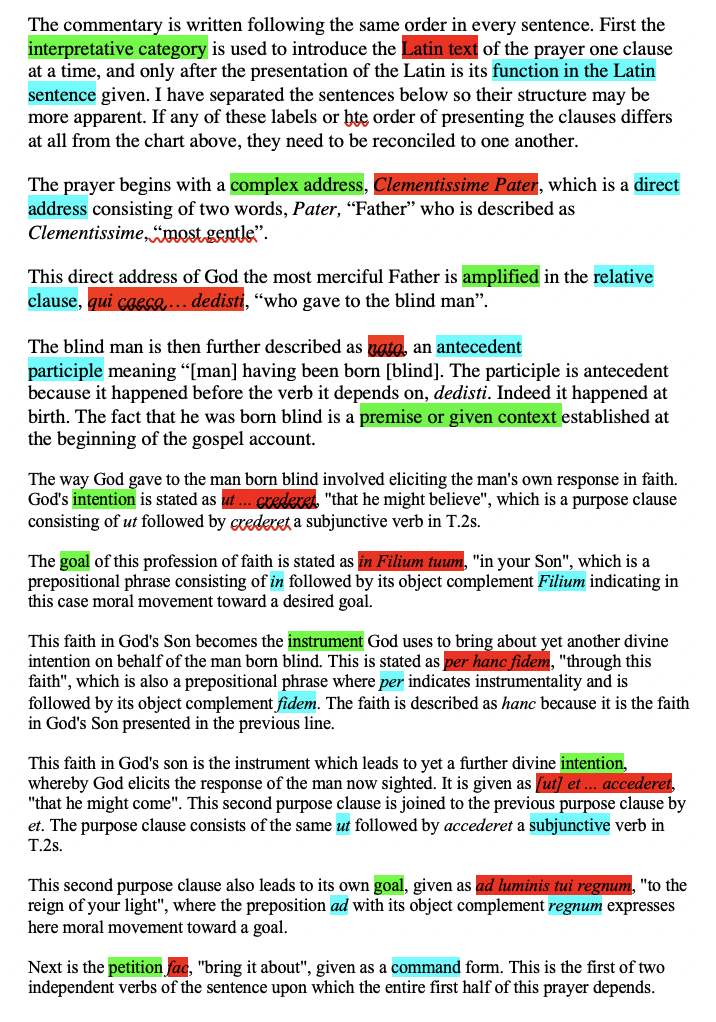

Writing a commentary on your prayer

- After having correctly drawn and labeled the boxes, and after drawing and labeling the tree, and after assigning the interpretative categories, having received the agreement of the moderator, then write the prose text that explains the structure of your prayer.

- If your prayer consists of more than one sentence, work one sentence at a time.

- Within each sentence, write on one clause at a time, one verbal form with its attendant words, one phrase at a time.

- I typically organise my writing according to the order of the clauses in the prayer, as represented in the chart of interpretative categories.

- On occasion it has been necessary to my writing according to the order of the verbal forms in the tree. In this case begin with the main trunk of the tree. Next move to the major branches which spring from the trunk. Next move to the lesser branches and so on.

- I write in this way:

- I prefer to begin each sentence with one or a few English words, rather than beginning with the Latin text from the prayer.

- These first few words lead to a statement of the interpretative category of the clause I’m writing about.

- Next I give the Latin text of the clause or phrase exactly as it appears in the prayer, but now in italic script.

- If you omit any words from the Latin text, remember to hold their place with an elipsis: space dot dot dot space such as, ut … crederet

- Next give the corresponding English rendering from the study text. I give it “in double inverted commas”.

- Next explain the function of the Latin phrase in the Latin sentence.

- This is followed by any commentary you wish to give on that phrase.

- In the example given below, I did not incorporate the official text of the prayer into the commentary. If you do so, you may incorporate it immediately after you give the study text, or after you have given your commentary on the text.

- Your commentary may include the following.

- Give the time of the verbal form, its relationship to other clauses, why you rendered it into English as you did.

- If you use any words which may not be familiar ot the reeader or which you are using in a technical way, please explain them, as I explain the use of the word “premise” in the example given below.

- Wherever you have difficulty figuring something out it is helpful to give the explanation so that the reader who has the same difficulty will follow your thought as well.

- When you give the official English rendering of the clause you may also offer some comment on how it expresses the Latin text.

- Comment on how your English rendering and the official rendering of the text are similar or different.

- Do not criticise the official rendering, but explain how it differs from the Latin.

- It is easy to develop a template for each sentence The template for each sentence is drawn from the columns of the chart above.It is easy to develop a template for each sentence

- give a draft rendering of the prayer in clear English. You may use the translation already published by the instructor.

The following two charts show how the text of the interpretative categories helps you to structure your commentary on each clause of the prayer.

Who does what to whom?

The next step is a form of semiotics. From this step we seek to understand the divine-human exchange in a prayer. We ask three questions:

- Who does it? = name the subjects (and the agents of passive forms)

- Who does what? = name direct objects

- Who does waht to whom? = name indirect objects

These three basic questions, however, are completed through several more steps. In order to prepare your page for this form of analysis, it is helpful to arrange your paper in landscape format, rather than portrait format. An explanation is given here for Microsoft Word.

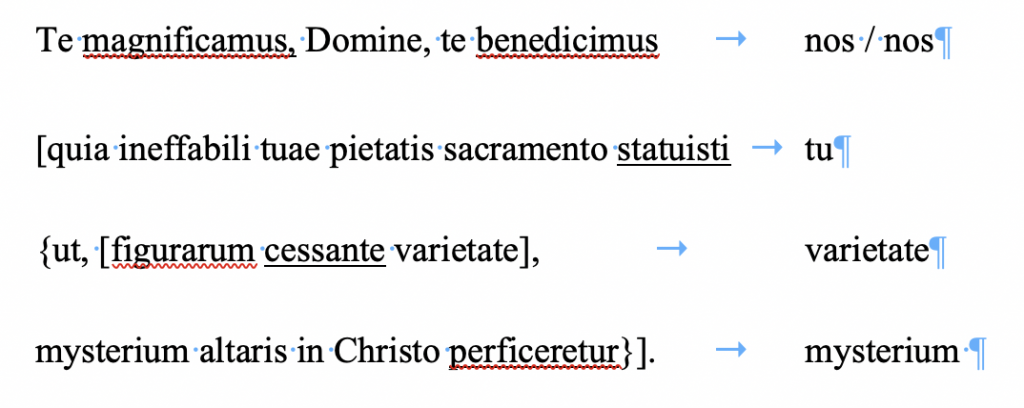

Who does it?

The text of the prayer is placed at the left margin of the page so that there is sufficient room to the right for drawing the charts. The prayer is to be arranged according to sense lines. Sometimes it is helpful to have extra space between the lines of text to accommodate the drawings. It may prove helpful to use the version of the prayer which has the underlined verbal forms and the brackets.

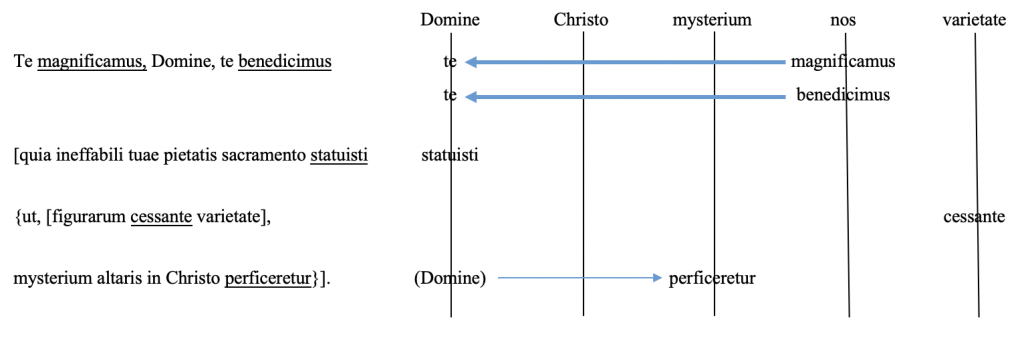

I. A. The first step is to name the subjects of each action word. Write the subjects of each verbal form in a column to the right. Each subject should be on the same line of text as its verbal form. The following is from the initial sentence of the dedication of an altar, research conducted by Anthony Etunwoke.

In the above image I have left the blue formatting to show so that you can see I am using tabs to establish the columns. Many students use spaces to adjust each word, but after they have progressed in their work and finally realise that they must return to the initial stages of this analysis and change something, they will be glad to have used tabs. Otherwise they will forever be aligning words using spaces.

I. B. After completing this first step, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

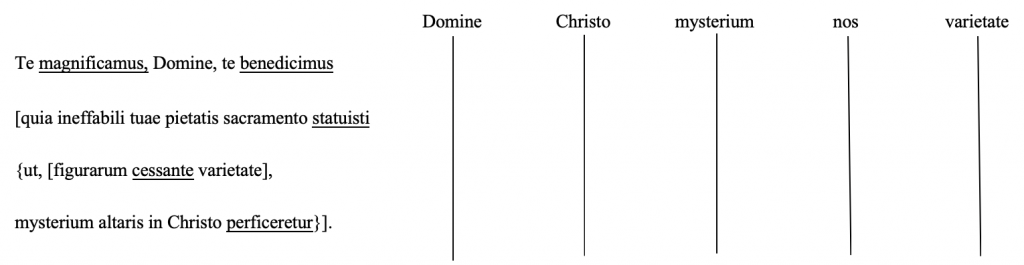

The next step is to sort the subjects and to assign a vertical column to each subject in the following manner.

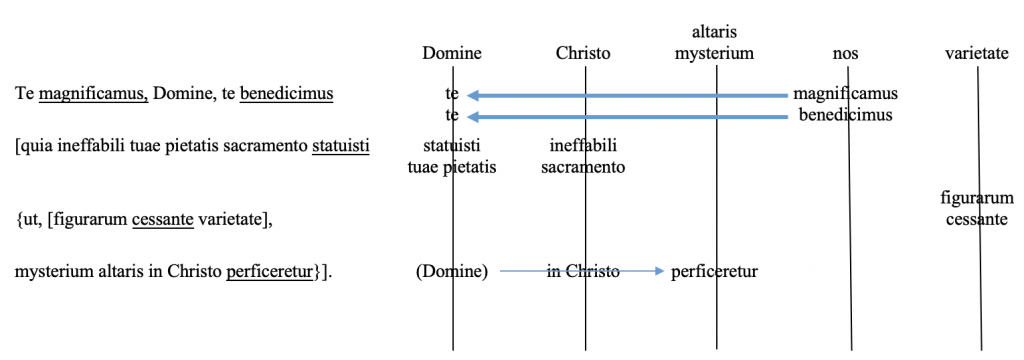

In the above chart I have assigned vertical columns to Domine, Christo, Mysterium, nos, varietate. We do not yet need a vertical line for Christo, but at the end of this process of analysis we discovered that we needed to add this vertical line, which I have labeled Christo, as it appears in the prayer.

When you draw the vertical lines, it may help to hold down the shift key which makes the lines run horizontally or vertically. Also notice that I am using tabs which centre the text on the vertical lines. It looks like this in the ruler:

The vertical arrow in the above image points straight up, indicating that the text will centre on the number 16. In the linked instructions for Microsoft Word you can choose “center”. You can also read this about tab-stop types.

I. C. After completing this step, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

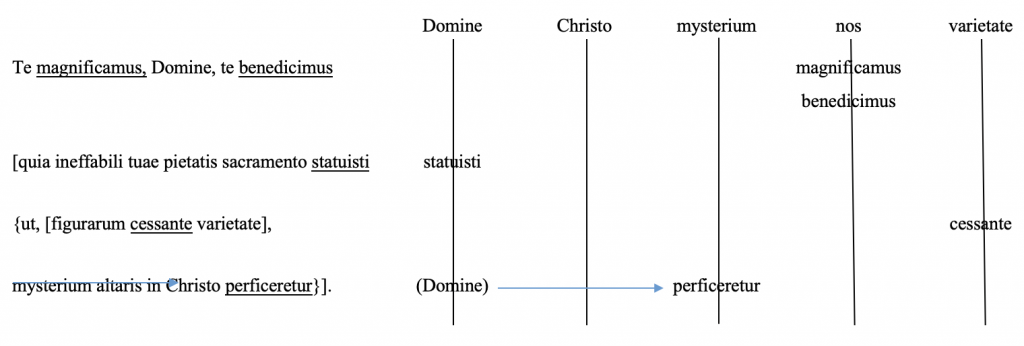

The next step is to write each action word on the vertical line corresponding to its subject as follows.

You can see that we have centred “magnificamus” and “benedicimus” on the vertical line for the subject “nos” because we are the subject of these two verbs. Domine is the subject for statuisti. Varietate is the subject for cessante according to the nature of an ablative absolute.

Passive verbal form which are truly passive and not simply deponent require an additional step. You can see that the subject of perficeretur is mysterium. This means that the mystery is acted upon by an unnamed actor. The mysterium undergoes a process done by another agent. We are inclined to think that the implied actor is God who brings to perfection the mystery of the altar. Thus we have indicated the hidden divine initiative by writing (Domine) in parentheses because only implied and centred on the vertical line for Domine. We have drawn a very thin arrow – I would prefer an arrow made up of dots or dashes – from (Domine) to the verb perfeceretur to indicate that Domine is the unnamed actor, or agent, working to bring to perfection the mystery of the altar.

Again, you can see the formatting arrows indicating that I am using tabs and each tab centres on the vertical line.

I. D. After completing this step, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

Because this is only the first sentence in a long prayer, it does not suggest itself for the next step, which I must illustrate using another prayer. A zig-zag line is drawn which shows the prominence of Divine initiative leading to the prominence of human action. Not every prayer is well suited to this pattern, but many are. Some prayers are more complex and can be divided into several parts and then the zig-zag pattern can be shown for each part of the prayer.

Who does what?

II. A. After completing this first series of charts, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

Erase the zig-zag pattern because you have preserved it above and it will only hinder your progress in successive steps.

This second question involves identifying the direct objects of the prayer. This prayer has only one but it appears twice.

In the above chart we labeled the direct object te twice on the vertical line Domine because te refers to Domine. Next we drew two arrows from the action words to their objects. These are heavier arrows than we used below to indicate the agent of the passive verb. These heavy arrows indicate direct action. They indicate that we are magnifying you O Lord: we, nos are magnifying, magnificamus, you, te, O Lord, Domine; and that that we are blessing you O Lord: we, nos are blessing, benedicimus, you, te, O Lord, Domine.

Who does what to whom?

III. A. After completing this step, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

The task at this stage of analysis is to identify the indirect objects in the prayer. Because this prayer does not have any, I shall have to use another prayer to illustrate the process.

In the above diagram you can see that the action of the verb passes through its object and continues on to its indirect object.

III. B. After completing this step, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

This step of analysis involves placing as much as possible the full text of the prayer into the diagram. Not all words are needed as you can see from the following chart.

We have added the words tuae pietatis on the line for Dominus because tuae refers to Dominus; the kindness is God’s. We have included ineffabili sacramento. We placed it on the line for Christo because at this point in our analysis it seems appropriate to associate Christ with the altar and the ineffable sacrament. If at a later stage of analysis we decide differently, we can go back and easily revise this and the previous charts.

In the above chart we also added in Christo and we superimposed it over the horizontal line indicating the hidden action of the Lord in bringing to perfection the mystery of the altar. We also added the words figurarum and altaris just to be more complete.

After completing this step, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

III. C. After completing this step, copy the entire chart and paste it further below on the page or on the next page. In this way you retain the previous versions of the chart and can return to adjust them and to more easily understand the prayer.

The final stage in this analysis asks once again the question of the divine-human exchange. Because this is only the first sentence of a much larger prayer, we have not taken this step here, but must illustrate the process with another prayer.

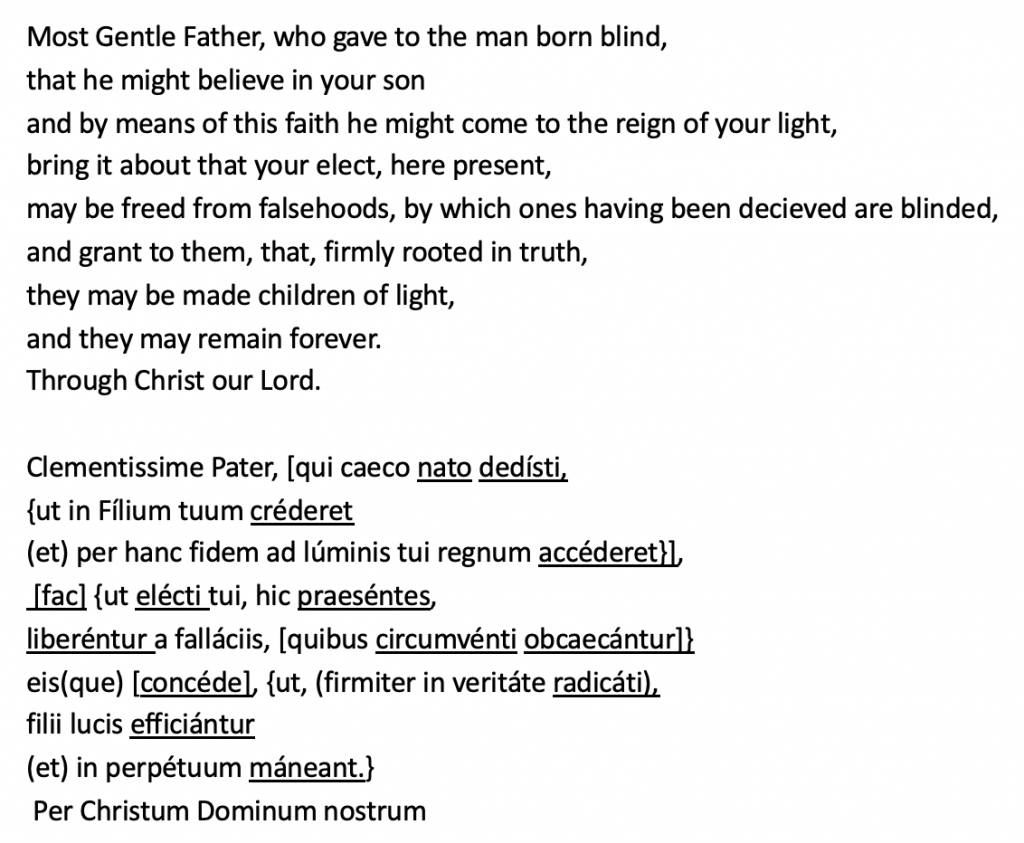

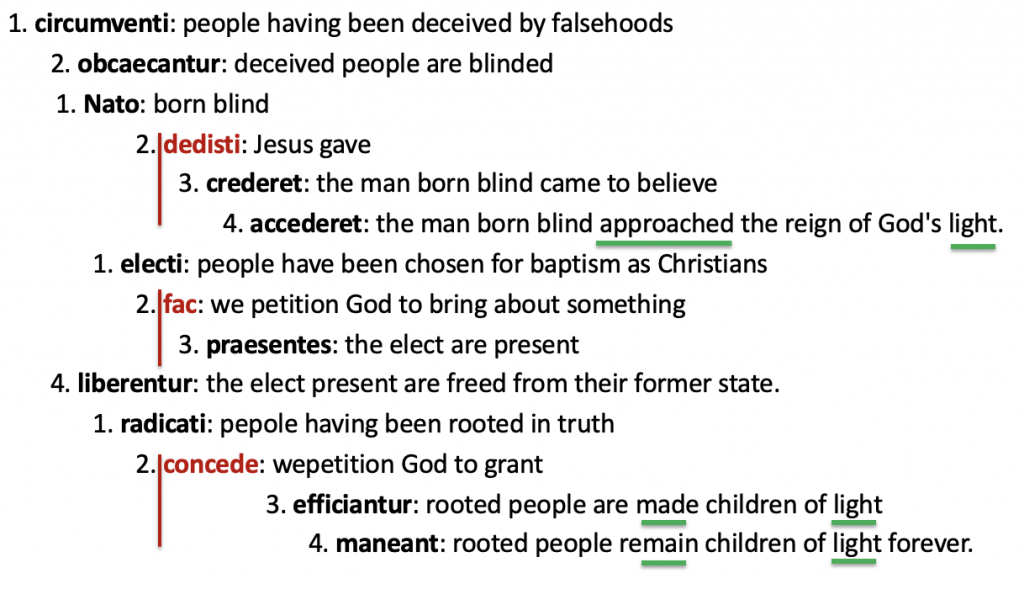

Human maturation

The process of human maturation can be mapped out in a parayer based on the timeline of actions in the prayer. We found an exceptional prayer, the first of two prayers which together comprise the second scrutiny celebrated on the fourth Sunday in Lent. First the text of the prayer is given with its translation below.

The timeline for this prayer is as follows:

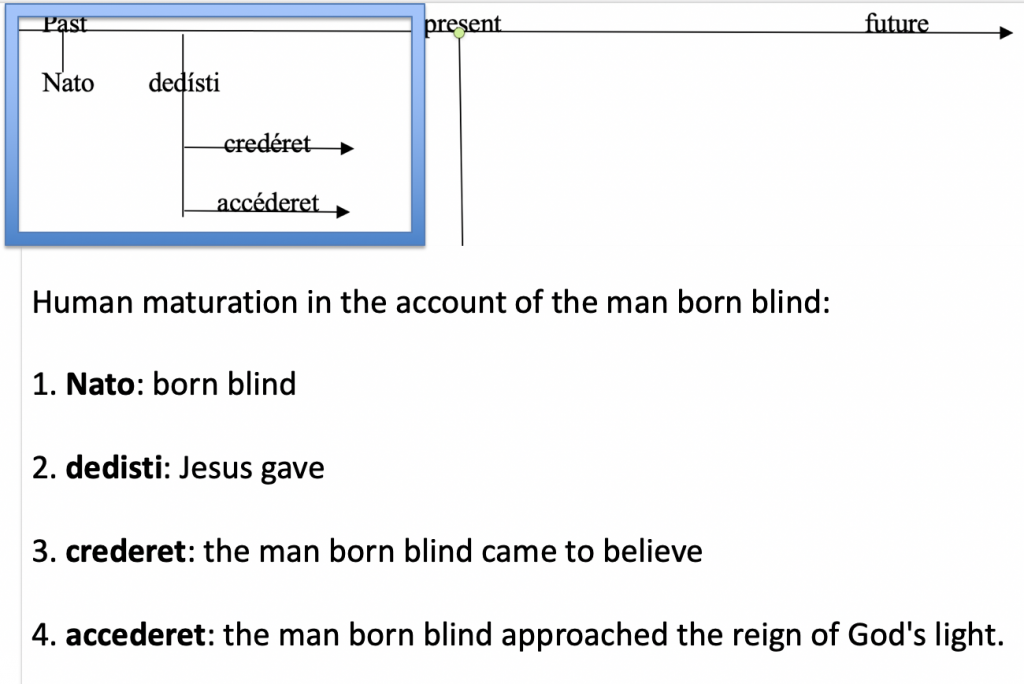

You can see in this timeline above that we have discerned four separate processes of human maturation. We shall consider each of them in the following analysis. They are:

- The human maturation of the man born blind given in the upper left and indicated by the blue box.

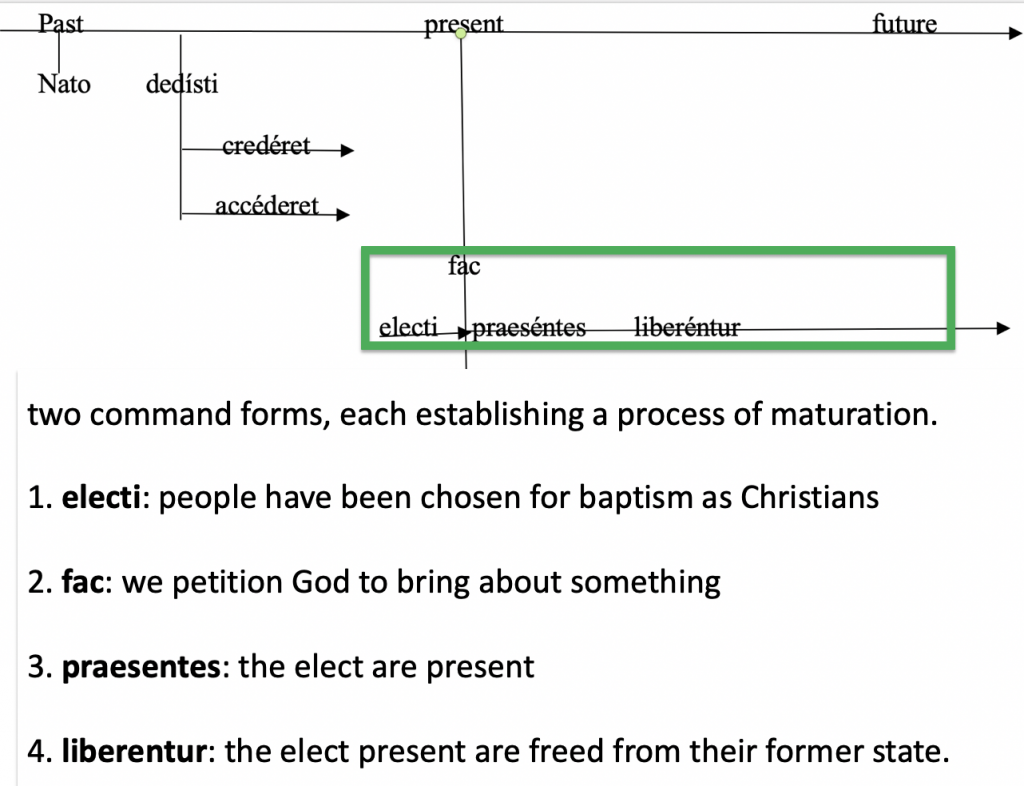

- Two command forms in this prayer establish two processes of human maturation. These are given in two green boxes.

- The state of humanity at the beginning of all of this is given in the yellow box.

First let us look at the process of human maturation of the man born blind.

The steps of human maturation are given in numerical order according to the order of the actions in the prayer over time. The earliest aciton to occur in this prayer was that the man was born blind, nato. Next Jesus gave to him, dedisti. Next the man came to believe, crederet, and finally he approached the reign of God’s light, accederet.

Next we shall see the human condition.

What happens in the case of the man born blind also occurrs on a grand scale for all of humanity. The human condition or the state of the world is given in the yellow box. This section does not indicate human maturation. Rather, it indicates that first people have been decieved by falsehoods circumventi. Next people are blinded by these falsehoods obcaecantur. This is the state of the man born blind when his narrative began, and this is the state of humanity.

Next we shall present the two processes of human maturation for which we pray. Each is established by a command form, expressing a petition.

The first action which occurrs in this series was the rite of election which occurrs typically on the first Sunday in Lent, electi. The next step is our petition for divine action, fac, “make, do, bring it about, cause …”. The next action is simply the presence of the elect, praesentes. Finally this series culminates with the liberation of the elect, liberentur. In a sense this first process of human maturation resolves the state of humanity, having been decieved and now blinded by falsehoods.

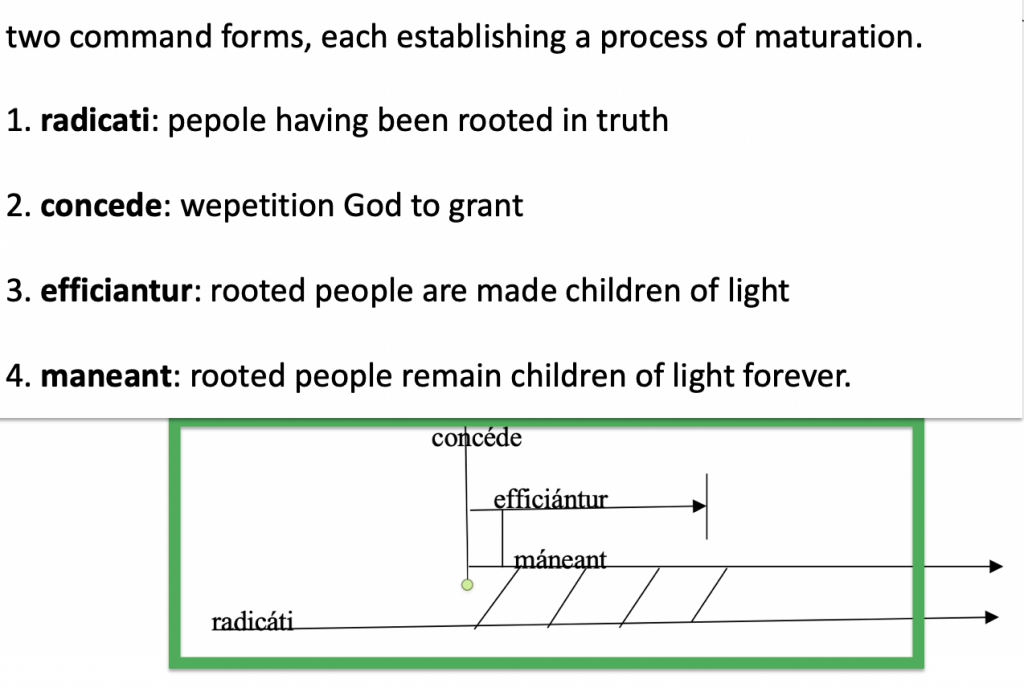

The final process of human maturation in this prayer superceeds them all.

The first action that happens in this process of human maturation is that the elect have been rooted in truth through the process of Christian initiation which has led them to this day, radicati. This process, however, does not end today. Rather it continues on in to the future whenever we become more firmly rooted in truth. The second step is our petition for divine action, that God grant, concede.

The third stage is that people rooted in truth are made children of light efficiantur. In a sense this surpasses the narrative of the man born blind who came to believe, as the elect become children of light.

The fourth and ultimate stage of human maturation is that the elect remain children of light forever. This surpasses the narrative of the man born blind who approached the reign of God’s light, as the elect become that light and remain thus forever.

For your ease of understanding, we have mapped these processes of human maturation over the Latin text of the prayer below.

And we do the same for the English text of the prayer below.

We have also produced a chart which attempts to relate these different processes one to another.

In the above chart, I have put the divine interventions in red letters. Jesus granted to the mann born blind, dedisti. We petition God to bring something about, fac, and to grant, concede. Actions which are spaced to the left of these divine interventions prepare for it. They include humanity having been deceived by falsehoods and being blinded in the present. This relates to the man having been born blind.

The first process of divine intervention in our lives is that the elect are liberated from the state of humanity, from falsehoods, from deception and from blindness.

The final process of human maturation surpasses them all and so are placed furthest to the right in the chart. These are the bottom two lines, where those rooted in truth are made children of light and remain thus forever. These are indicated with green underscore.

This process of human maturation prepares the scholar for the analysis of theosis.

Session 2: 23 February

We shall examine the four participles presented by the instructor:

See: Encounters 50-53

- contemporaneous active

- antecedent passive (antecedent active – deponent)

- futurity

- passive necessity

We shall progress in our analysis of the Latin text of the prayer given in the first encounter.

We shall examine the construction of the Ablative Absolute and its role in the sentence, and how to render it into clear English. See: Encounters 54-57

We shall begin to apply a basic semiotic analysis to the prayers asking the following three questions, being mindful of both active and passive events:

- Who does it?

name the subjects

name the subjects and agents of passive forms - Who does what?

add the objects and object sentences (note the 65 and compound verbs) - Who does what to whom?

add the indirect objects, ablative and other elements

We shall draw a chart to answer the first question. From this initial chart we may gain a general understanding of the divine-human exchange in the prayer.

We shall copy the first chart and add to it the answers to the second question.

We shall copy the second chart and add to it the answers to the third question.

From this analysis, we shall develop an interpretation of the divine-human exchange in the prayer. See: Appreciating the Collect; Transition in the Easter vigil

Session 3: 2 March

We shall consider the mode of speaking in indirect discourse, and the function of object sentences.

We shall consider the performative steps of a collect type prayer:

1. invitation to pray

2. silence for personal prayer

3. prayer offered by the minister

4. ratificaiton of the prayer by the assembly: “Amen”.

See: De Zan; Appreciating the Collect; Listen to the Word

We shall also consider the ritual programme of the collect as the conclusion of the entrance rites and preparation to listen to the Word and to continue the procession toward shared communion. See: REGAN, P., “The Collect in Context”, in Appreciating the Collect, ed. Leachman, St. Michael’s Abbey Press, Farnborough 2008. See also: McCarthy, D.P. – J.G. Leachman, Come into the Light, Canterbury Press, Norwich 2016.

We shall consider the collect for the Sixth Sunday in Lent

We shall conclude our presentation of the Latin expression of the collects by considering the function of the gerund in the prayer.

We shall next begin the second half of the course which will focus on the four interpretative keys for understanding a ritual action, or in this case a collect offered in its ritual context. We present each of these four interpretative keys as a pair:

Anamnesis in collects

anamnesis is understood according to the presentation of Prof. De Zan in terms of the narrative of the saving works of God and celebrating the ritual programme. See: D.P. McCarthy, “Between Memories and Hopes: Anamnesis and Eschatology in selected collects”, Appreciating the Collect; see also: Transition in the Easter vigil, pp. 124-127; see also: J.G. Leachman – D.P. McCarthy, “A Liturgical Study of the proper prayers for St Charles of St Andrew Houben, C.P. 1: The Opening Prayer”, Questions Liturgiques: Studies in Liturgy 92 (2011) 28-44, especially 40-41.

One aspect of eschatology is maturation. The initial presentation of our understanding of maturation was given in a paper: J.G. Leachman, “A New Liturgical Hermeneutic: Christian Maturation by Developmental Steps”, New Blackfriars 90 (2009) 219-231. Some initial examples are given in this chapter: D.P. McCarthy, “Between Memories and Hopes: Anamnesis and Eschatology in selected collects”, Appreciating the Collect. The pastoral concern for the maturation of the liturgical assembly is duscussed in the doctoral thesis: M. Glowasky, Rhetoric and Scripture in Augustine’s Homiletic Strategy: Tracing the Narrative of Christian maturation (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae: Texts and studies of early christian life and language 166) Brill, Leiden – Boston 2021.

Epiclesis in collects

Epiclesis is understood in terms of the presentation of one’s self to God in prayer at the prompting of the Holy Spirit, and the invocation of God. As we process to meet Christ the one coming, this double procession leads to an encounter in which the human person is changed in the following two ways. See: Transition in the Easter Vigil, pp. 123-124; see also: Leachman, “A Liturgical Study of the proper prayers”, 39-40; Two important volumes are: J. McKenna, The Eucharistic Epiclesis: A Detailed History from the Patristic to the Modern Era, Liturgy Training Publications, Chicago 2 2008; A. McGowan, Eucharistic Epicleses, Ancient and Modern: Speaking of the Spirit in Eucharistic Prayers (Alcuin Club Collections 89), Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), London 2014; C. Kappes, The Epiclesis Debate: at the Council of Florence, University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, Indiana 2019.

Two other studies to note: R.F. Taft, “From logos to Spirit: On the early history of the epiclesis”, Gratias agamus. Studien zum eucharistischen Hochgebet für Balthasar Fischer, ed. A. Heitz – H. Rennings, Herder, Freiburt – Basel – Vienna 1992, 489-501; R.F. Taft, “The Epiclesis question in the light of the Orthodox and Catholic lex orandi traditions”, New Perspectives on Historical Theology. Essays in memory of John Meyendorff, ed. B. Nassif, W.B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids – Cambridge 1996, 210-237.

Eschatology in collects

Eschatology is the graced process of transcending one’s former self in order to become one’s self anew in a greater communion. By such stages of human maturation a person cooperates in one’s own graced transformation into the body of Christ. This is lived in daily life, according to the Gospel of Matthew chapter 25, by our moral behaviour in the world. See: D.P. McCarthy, “Between Memories and Hopes: Anamnesis and Eschatology in selected collects”, Appreciating the Collect; see also: Transition in the Easter Vigil, pp. 127-128; see also: Leachman, “A Liturgical Study of the proper prayers”, 41-42.

Volumes I have yet to consult are: The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology, ed. J.L. Walls (Oxford Handbooks in Religion and Theology), Oxford UP, Oxford 2010; M. Mühling, T&T Clark Handbook of Christian Eschatology, Bloomsbury T&T Clark, London – New York 2015; G. Wainwright, Eucharist and eschatology, Epworth Press, Peterborough 2003.

Theosis in collects

Theosis is the graced experience of coming to full human personhood, that is to share on a human level in the personal way of being proper to the Divine Trinity. This is experienced in the personal exercise of freedom in a bond of love.

For the discussion of Theosis, see the comments of Norman Russell on the contribution of John Zizioulas in:

- N. Russell, The Doctrine of Deification in the Greek Patristic Tradition (Oxford Early Christian Studies), Oxford UP, Oxford 2006, 318.

- See also: Transition in the Easter Vigil, pp. 333-38;

- see also: Leachman, “A Liturgical Study of the proper prayers”, 5.1 on page 39, 5.5 on pages 42-44.

Several related volumes:

- J.D. Zizioulas, The Eucharistic Communion and the World, ed. L.B. Tallon, Continuum (T&T Clark), London – New York 2011.

- C. Yannaras, The Freedom of Morality (Contemporary Greek Theologians 3), tr. E. Briere St. Vladamir’s Seminary Press: Crestwood, New York 1984.

- C. Yannaras, Relational Ontology, tr. N. Russell, Holy Cross Orthodox Press: Brookline, Massachusetts 2011 (of Ontologia tēs schesēs, Ikaros, Athens 2004).

- C. Yannaras, Person and Eros, tr. N. Russell, Holy Cross Orthodox Press: Brookline, Massachusetts 2007 (of To prosopo kai o eros, Athens 1987).

- C. Yannaras, Variations on the Song of Songs, tr. N. Russell Holy Cross Orthodox Press: Brookline, Massachusettes 2005 (of Scholio sto asma asmatōn,

For theosis in the Latin authors see:

- D.V. Meconi, One in Christ: St. Augustine’s Theology of Deification, Catholic University of America Press, Washington D.C. 2018.

- J. Ortiz, “Making Worshipers into Gods: Deification in the Latin Liturgy”, in Deification in the Latin Patristic Tradition, ed. J. Ortiz, Catholic University of America Press, Washington DC forthcoming;

- G. Ladner, The Idea of Reform: Its Impacton Christian Thought and Action in the Age of the Fathers, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass 1959, 133-316;

- G.M. Lukken, Original Sin in the Roman Liturgy: Research into the Theology of Original Sin in the Roman Sacramentaria and the Early Baptismal Liturgy, Brill, Leiden 1973, 73-74.

Two other books I have consulted: Theōsis:

- Deificaiton in Christian Theology, ed. S. Finlan – V. Kharlamov (Princeto Theological Monograph Series), Pickwick Publications, Eugene Oregon 2006.

- Partakers of the Divine Nature: The history and development of deification in the Christian tradition, ed. M.J. Christensen – J.A. Wittung, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids Michigan 2007.

In this session we shall begin to consider the interpretative key of anamnesis.

Session 4: 9 March

We shall continue our considration of anamnesis in this encounter. See: D.P. McCarthy, “Between Memories and Hopes: Anamnesis and Eschatology in selected collects”, Appreciating the Collect; Transition in the Easter vigil

We shall examine the collect for the Eighth Sunday of Easter

We shall turn our consideration to the interpretative key of epiclesis. See: Transition in the Easter vigil

Session 5: 16 March

This collect will guide our consideration of the interpretative key of eschatology. We shall also consider how the collect presents steps of human maturation. See: D.P. McCarthy, “Between Memories and Hopes: Anamnesis and Eschatology in selected collects”, Appreciating the Collect; Transition in the Easter vigil

This collect will guide our consideration of theosis. see the comments of Norman Russell on the contribution of John Zizioulas in N. Russell, The Doctrine of Deification in the Greek Patristic Tradition (Oxford Early Christian Studies), Oxford UP, Oxford 2006, 318. See also: Appreciating the Collect; Transition in the Easter vigil

Session 6: 23 March

During the final sessions of our course, we shall review all that we have learned by examining a different collect during each session.

If one of the previous classes is for any reason cancelled, that session and all the subsequent ones will be considered in turn, and the loss of a session will be made up by omitting this last review session.

Collects for Sundays in Lent and of Easter which are not slated for consideration are the following. If time were to permit, they may so be considered, and so are included in your packet of material:

Materials continued

You may purchase our books from Sr. Bernadette or the English desk at:

Pauline multimedia

via del Mascherino, 94

00193 Roma

Tel. 06.6872354

Fax: 06.68308093

Sr. Bernadette: Inglese@paoline-multimedia.it

General enquiries: centro@paoline-multimedia.it

www.paoline-multimedia.it

Map:

Latin resources

I have begun to develop a page of resources for the Latin language including: dictionaries, grammars, resources, texts, links.

Online free, more:

Classical Works Knowledge Base:

http://cwkb.org

Another I have found is Neumen: The Latin Lexicon:

http://latinlexicon.org/index.php

© 6 February 2021 by Daniel McCarthy